A NOVEL IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR PREVENTING POST-STROKE DEMENTIA

HOW TREATING INFLAMMATION IN THE BRAIN FOLLOWING STROKE CAN PREVENT PATIENTS FROM DEVELOPING DEMENTIA.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States. Every year, more than 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke, and nearly 1 in 20 deaths are caused by them (1). Aside from the high mortality rate of strokes, they can also cause lasting brain damage and long-term disability in survivors. In fact, approximately one third of patients that suffer from a stroke will eventually develop vascular dementia, which can cause a wide array of cognitive deficits including memory loss, confusion, language problems, impaired motor skills, and difficulties performing everyday tasks. While some medications can help slow dementia after a stroke, little is understood about what causes it. However, a recent study by the Buckwalter Lab at Stanford University indicates that antibodies targeting a certain protein on brain cells may play a role in the development of vascular dementia, and work in the lab suggests that eliminating these antibodies may help prevent the development of post-stroke dementia.

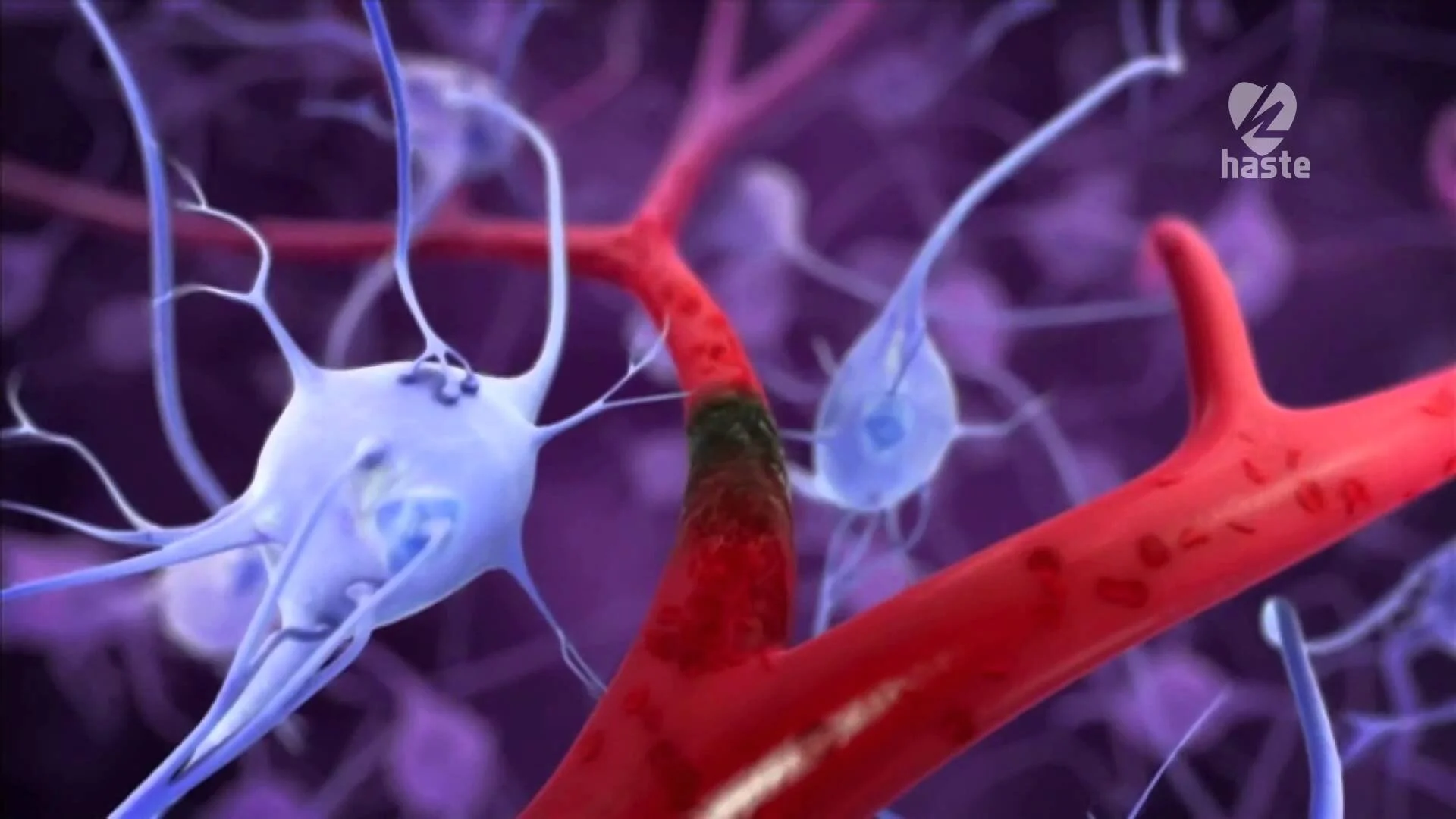

Strokes occur when blood flow to part of the brain is blocked, depriving nearby brain cells of oxygen and resulting in their death (1). The initial signs of a stroke include sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding others, vision disturbances, loss of balance or coordination, sudden headache, and sudden numbness of the face, arms, or legs. The symptoms that occur long-term following a stroke, though, depend largely on the part of the brain that was affected. While the initial stroke may be responsible for some of these long-term symptoms, an increased risk of cognitive decline exists for at least a decade after the stroke, indicating that something other than an initial rapid loss of brain cells is to blame for post-stroke dementia.

In their February 2016 publication in the Journal of Neuroimmunology, the Buckwalter Lab identified an increased number of immune proteins called antibodies that specifically targeted and removed myelin basic protein (MBP; a common protein found on brain cells) in the blood of patients who experienced cognitive decline following stroke compared to patients who did not experience cognitive decline (2). Importantly, they did not find an increase in antibodies specific to other brain proteins, suggesting that antibodies specific to MBP may be particularly important for worsening cognition following stroke. While this study was correlative and thus unable to determine whether antibodies were the direct cause of cognitive decline following stroke, previous work by the Buckwalter Lab indicates that this may in fact be the case.

In February 2015, the Buckwalter Lab published a paper in the Journal of Neuroscience indicating that some patients develop an increase in the number of antibodies in the brain following a stroke and, in mice, this response was directly responsible for cognitive decline (3). In their study, the research group also observed that the brains of patients with stroke and dementia contained higher numbers of B cells, which produce antibodies, than did the brains of people who had not suffered from either of these afflictions.

The group then used a novel mouse model of post-stroke dementia to demonstrate that immune cells including T cells, B cells, macrophages, and microglia are present at the site of the stroke 7 weeks following the stroke. Additionally, they observed increased levels of multiple classes of antibodies within the stroke lesion, suggesting that the B cells producing them were activated and targeting a specific protein, though that protein is not identified in this study. Because the immune response in the brain was delayed and occurred long after the initial stroke, they hypothesized that the immune response to the stroke (rather than the initial stroke itself) could participate in long-term cognitive decline.

Importantly, when mice sustained strokes, they experienced cognitive decline within 7 weeks, and this deficit remained even 12 weeks after the stroke, which was the last time point tested. However, mice genetically engineered to lack B cells did not experience cognitive decline following stroke even though the rest of the immune response remained unchanged. These findings suggest that B cells and the antibodies that they produce play an important role in facilitating post-stroke dementia.

Although humans cannot be genetically engineered to lack B cells, there are drugs that can impair the activity of B cells or even deplete them entirely. Notably, rituximab is a B cell-depleting drug that is currently FDA-approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis. In their 2015 Journal of Neuroscience paper, the Buckwalter Lab demonstrated that treating mice with rituximab following stroke was sufficient to prevent these mice from developing post-stroke dementia, thus indicating that treating patients with rituximab following stroke may also prevent them from developing dementia later in life.

Eliminating B cells by treating with rituximab may not be the best solution in all cases, though, because B cells are an important part of the immune response against infectious diseases like bacteria and viruses. Rituximab may therefore weaken patients’ immune systems and make them more susceptible to infection, which can be especially dangerous for elderly and hospitalized patients who represent the majority of people who experience strokes. Additionally, not all patients who experience a stroke go on to develop an immune response in their brain or cognitive impairment later on in life, meaning treatment with rituximab could be an unnecessary risk for these individuals. It is therefore necessary to first identify patients who would benefit from B cell depletion before beginning treatment with rituximab. Luckily, it has recently been shown that a radioactive form of rituximab can be used to image B cells in patients using PET imaging (4). Therefore, PET imaging may be able to identify which patients have B cells in the brain following stroke and thus which patients are the best candidates for receiving rituximab.

While it appears that rituximab may prove beneficial in the prevention of post-stroke dementia, many questions regarding the underlying mechanisms of post-stroke dementia still remain. For instance, it is unknown if B cells, as well as the antibodies that they produce, are solely responsible for the development of dementia in humans or if other mechanisms may be involved. Further, the role of other immune cells in the brain following stroke has yet to be determined, and it is unknown whether these cells may also participate in the development of post-stroke dementia in humans. Rituximab may be insufficient to prevent all stroke patients from developing dementia, but future studies will provide a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying post-stroke dementia and the treatment options that are most effective in combatting it.

REFERENCES

CDC, NCHS. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2013 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2015.

Becker, et al. Antibodies to myelin basic protein are associated with cognitive decline after stroke. Journal of Neuroimmunology 295-296:2016.

Doyle, et al. B-Lymphocyte-Mediated Delayed Cognitive Impairment following Stroke. Journal of Neuroscience. 35(5):2015.

Tran, et al. CD20 antigen imaging with (1)(2)(4)I-rituximab PET/CT in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Antibodies 20(29-35):2011.