DO YOU FEEL THE BURN? THE SCIENCE BEHIND YOUR SPICE TOLERANCE

THE KEY TO ENJOYING SPICY FOODS? IT'S ALL IN THE ATTITUDE

Contrary to popular belief, you cannot permanently destroy your taste buds. Eating spicy foods can hurt your tongue and make you less able to perceive the spice, but your taste receptors won’t be gone forever— the effects of desensitization only last a few days. Instead, new research shows that genetics and personality play a much bigger role in our spice tolerance than the taste receptors on our tongues.

GENETICS OF SPICE TOLERANCE

Genetically, some people are born with fewer receptors for capsaicin, which is the compound that makes hot foods taste and feel hot. These individuals are less able to taste capsaicin-derived spiciness, which gives them an above average built-in tolerance for heat. Some people also experience the reverse and are born with more taste buds, so they experience a stronger sensation of spicy heat.

Researchers studied twins to determine if the genetic component of spice tolerance was quantifiable. Identical twins, who share the same DNA and home environment, and fraternal twins, who do not have the same DNA but do share the same life experiences, were fed strawberry jelly spiked with capsaicin. The study concluded that genetics account for 18-58% of humans’ spice tolerance, as identical twins were more likely to show matching spice preferences (1). While that is a wide range, it means that at least 18% of your personal penchant for peppers is out of your control.

It’s important to note that upbringing and exposure to capsaicin at a young age can also influence spice tolerance over a person’s lifetime. Regularly consuming spicy food as a child can desensitize nerve endings on the tongue and decrease sensitivity. Many cultures have cuisines rich in capsaicin-containing peppers, and children from these cultures are more likely to have higher spice tolerances as adults.

PERSONALITY AND SPICE TOLERANCE

A person’s attitude towards spice is also a key component for their sensitivity, as it affects their enjoyment. Cultures featuring capsaicin-rich foods likely make positive associations with spice, which get passed on to children. This is a phenomenon known as “context effect,” where repeated consumption can change an individual’s internal guide as to what is and is not spicy (2). Context effect is the most robust way to increase your spice tolerance as an adult, much more so than simply continuing to eat hot foods. In the twin study, the researchers found that a shift in preference for the burning/stinging sensation elicited by spicy food was the primary non-genetic predictor of spice tolerance. The twin study participants also completed a questionnaire to assess their food preferences and personalities. Logically, scores for “pleasantness of spice, spicy food, and pungent sensations” showed that the individuals who consumed spicy food more frequently found it more pleasurable (1). This makes sense because we tend to eat the foods we like more often than foods we don’t like.

A person’s natural personality, as shaped by both genetics and environment, plays a key role in the enjoyment and consumption of spicy foods (3). Participants who showed more risk-taking and thrill-seeking tendencies in the questionnaire were overwhelmingly more likely to enjoy eating spicy foods and feeling the accompanying burn (1, 3). Just as some people enjoy the adrenaline of jumping out of a plane while others find the idea horrible, the same goes for the sensation that accompanies eating capsaicin-heavy, spicy food.

HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR SPICE TOLERANCE

The non-genetic differences between individuals with difference spice preferences showed that increasing one’s ability to eat spicy food is less about building physical tolerance, and more about changing one’s attitude towards it. Some individuals are more likely to enjoy the the burning effects of capsaicin, which is likely due to their thrill-seeking personalities. However, long-lasting spice tolerance can be built over time using the fake it till you make it attitude, instead of trying to grin and bear it.

REFERENCES

Törnwall, O. et al. Why do some like it hot? Genetic and environmental contributions to the pleasantness of oral pungency. Physiology & Behavior 107, 381-389 (2012).

Tommy, N. Do genetics shape your spicy-food threshold? First We Feast (2016). https://firstwefeast.com/features/2016/05/spicy-genetics-investigation/.

Byrnes, N. K., and Hayes, J. E. Personality factors predict spicy food liking and intake. Food Quality and Preference 28, 213-221 (2013).

O’Neill, J. et al. Unravelling the Mystery of Capsaicin: A Tool to Understand and Treat Pain. Pharmacological Reviews 64, 939-971 (2012).

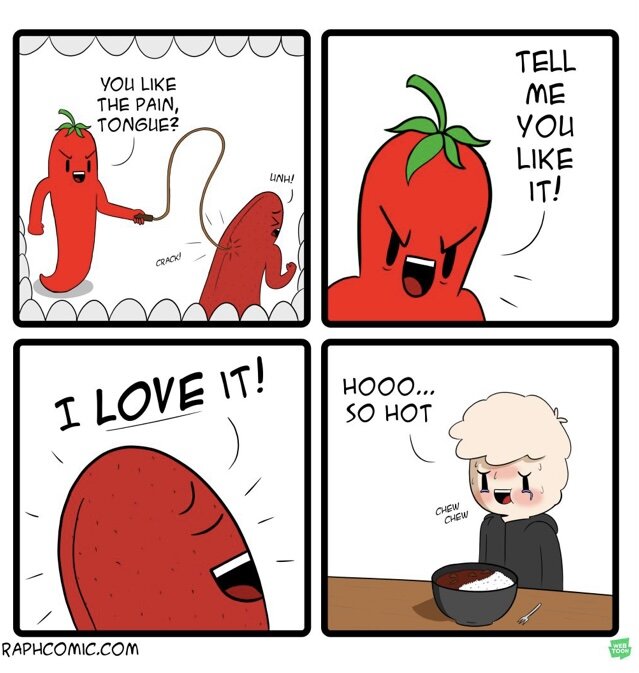

Raph. Spicy. 19 July 2018. RaphComic. https://raphcomic.com/comics/spicy.