FROM BOMBS TO BLOOD: THE EVOLUTION OF STEM CELL BIOLOGY

Stem cells are a hot topic. They frequently come up in conversations: from the high hopes we have for the development of new stem cell therapies to the ethics of embryonic stem cell research. We talk about stem cells a great deal, but what exactly are they?

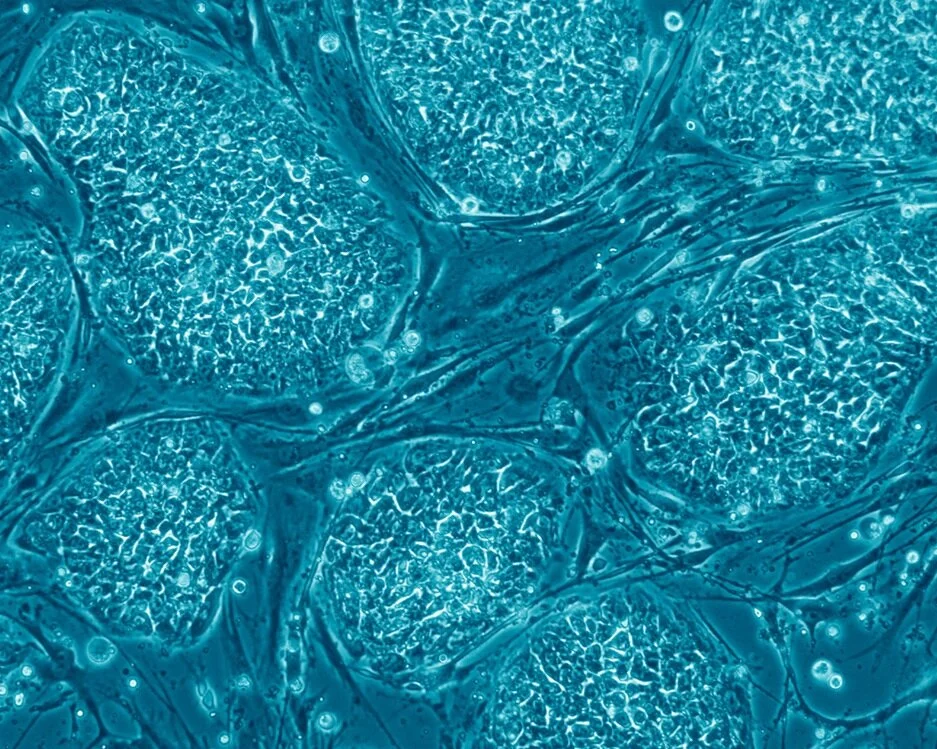

Stem cells are a special type of cell that divide to make identical copies of themselves and are able to turn into one or more different cell types. Humans and other animals have many different types of adult stem cells present in our bodies.

Destruction Shedding Light on Life

How stem cells were first discovered will likely come as a surprise. The first evidence for the existance of stem cells came following the droppings of the atomic bombs in World War II.

The dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II resulted in unprecedented destruction and loss of life. In the days to weeks following the bombing, victims began dying in a second wave, not from injuries or burns sustained from the blast itself, but from mysterious symptoms which included hair loss, low white blood cell counts, and in some cases, destruction of the stomach and intestinal lining. This caused scientists to look into why these people were dying, and they discovered radiation to be the culprit (Armstrong et al. 2011 Stem Cells). Radiation injures cells, causing cell death and interfering with the cell’s ability to divide to make new cells. Without cells that can divide and form new cells, body parts like hair and blood can not be regenerated. Early radiation experiments thus led to the discovery of stem cells, specifically hematopoietic stem cells (blood-making stem cells; Till & McCulloch. 1961 Radiation Res; Becker, Till, & McCulloch. 1963 Nature).

Hematopoietic stem cells produce all the different types of blood cells and continuously replace lost blood cells. In fact, all the red blood cells in your body are completely replaced every three months! The reason why we need to replace these cells at such a high rate is because they get beat up while they are circulating in the body. This constant wear and tear on the blood cells leads to their eventual death. If we did not have a way to replace these lost blood cells we would have less and less of them, which would lead to severe anemia and eventually death. It’s a good thing that we have hematopoietic stem cells to make sure this doesn’t happen!

Stem Cells as a Therapy

There are only a handful of stem cell therapies currently on the market. The most common one is bone marrow transplantation to replace hematopoietic stem cells, which reside in bone marrow. If something is wrong with your hematopoietic stem cells, we have the ability to give you new ones! This procedure involves killing off the patient’s original hematopoietic stem cells with low level radiation (hematopoietic stem cells are more sensitive to radiation than most other stem cells) and then replacing them from stem cells in donor bone marrow.

Bone marrow transplants are used to treat a variety of diseases including leukemia and some autoimmune diseases. To increase the chances of a successful bone marrow transplant, patients are matched with a donor in the donor bone marrow database based on a variety of factors. If you are interested in becoming a bone marrow donor, please check out Be The Match.

###The Explosion of the Field of Stem Cell Biology Although current stem cell therapies are limited in scope, there have been a lot of advancements in the field of stem cell biology in the last two decades. A major contributor to the rapid advancement of stem cell biology was the development of embryonic stem cell lines in 1998 (Thomsan et al. 1998).

These cells are a great tool that allow scientists to better understand stem cell biology and biological development. In the laboratory, scientists have been able to induce embryonic stem cells to become different cell types by treating these stem cells in different ways, thereby allowing research of how cells turn into other cell types (NIH Stem Cell Basics).

Stem cells can also be used to model diseases in adult human cells with the goal of developing new therapies to treat them. For example, embryonic stem cells can be turned into neurons that are used to identify new drugs to treat Lou Gehrig's Disease, a disease in which patients gradually lose the ability to move their body. The hope for embryonic stem cells is to use them to produce various cell types that can then be transplanted into patients to treat diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, vision loss, and spinal cord injury. They are an irreplaceable human model system that aids in the advancement of our scientific understanding as well as in the development of new therapies and treatments for diseases.

The Development of Embryonic Stem Cell Lines and the Alternatives

Embryonic stem cell lines are created five days after sperm fertilizes the egg. At this time point the embryo is composed of 200 cells of which the role of 85% is to provide nutrients to the developing embryo (Thomsan et al. 1998). Only 30 – 34 cells at this stage will eventually give rise to the organism. Research using these embryonic stem cell lines has never been prohibited in the US (although federal funding was briefly limited to select lines from 2001 – 2009). The ethics of the development of embryonic stem cells is outside the scope of this article. If you are interested, more on the topic of the ethics of embryonic stem cells can be found here.

A companion to embryonic stem cells are induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These are cells that have been taken from an adult and turned into an “embryonic-like state”. For example, skin cells from a patient can be taken and converted into a younger, unspecified cell type that then has the capability of making all cell types in the adult body. However, there are differences between the embryonic stem cells and iPSCs. In particular, iPSCs are not an entirely clean slate. They maintain a memory of the adult cell type that they used to be. This makes it easier to turn them back into that original cell type, but more difficult to turn them into different cell types.

Another difference is that iPSCs can be created from the patient’s own cells. If these are then used in a treatment in which the patient receives the cells back, there would be a lower risk of the patient rejecting the cells because they are the patient’s own cells. This has caused many people to be excited for the potential of iPSCs in personalized medicine. However, the time and cost to make iPSCs makes it difficult to turn iPSCs into personalized stem cell therapies. It is easier, faster, and more cost effective to have a bank of non-patient-specific iPSCs or embryonic stem cells that can be used in stem cell therapies.

Looking Forward

In the US, there are no approved stem cell therapies apart from bone marrow transplants and its derivatives. However, there are several clinical trials for stem cell therapies using iPSCs or embryonic stem cells that are currently being conducted globally. It takes time to ensure the safety and viability of new treatments. New stem cell therapies using iPSCs or embryonic stem cells may come to market within the next decade.

A major challenge with using iPSCs or embryonic stem cells as a therapy is to make sure that they are safe to put back into humans. It is important to make sure that if these cells are used to make other types of cells for a patient that these cells don’t do anything unexpected when introduced to the body or cause harm to the patient. The unwanted cells that don’t fully turn into the desired cell type also need to be eliminated. Scientists are currently working towards solutions for these problems. Their research will find ways to use stem cells to help develop safe new medical treatments.

References

Armstrong L, et al. (2012). Editorial: Our Top 10 Developments in Stem Cell Biology Over the Last 30 Years. Stem Cells. 30(1): 2-9.

Becker AJ, JE Till, & EA McCulloch. (1963). Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells. Nature. 197: 452-4.

Thomson JA, et al. (1998). Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science. 282(5391): 1145-7.

Till JE, & EA McCulloch. (1961). A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiation Research. 178(2): 213-22.