CELL MECHANIC

MAKING MINIMAL LIFE

How would you figure out how a car works? If you knew the model of the car maybe you could search online for a car manual. If the manual were missing a component you could call the engineers who built it and ask them. As biologists we don't have this luxury. We find life as it is - working but with no manual or engineer to consult.

Without the manual an approach you can take is to start removing parts. If you're interested in what makes your car move, you could see if taking out the back seats affects forward driving. What about the windows? The mirrors? Maybe you would become adventurous and take out the wiper-fluid lines. You would learn that all of these changes would not affect the running of the car - they just remove some inessential features. When you start to remove parts of the engine though, you would find that these are essential for the car to run. Running these experiments, each time taking off more and more of the car while still allowing it to run, would lead you to make a "minimal car"- a car that has just enough components to run but nothing more.

Scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) took this approach to understanding bacterial life in a recent paper. Specifically they wanted to know how small they could build a genome to make a minimal genome. For our purposes a genome is like a library. Inside of this library are different sets of instructions - called genes. Your genes are composed of DNA, which codes for the machinery within cells. For instance there are genes that deal with cell metabolism, how the bacterium eats and gets rid of waste. Another set of genes deals with how the bacterium makes more copies of its genome. Yet another set deals with how the bacterium makes its cell membrane, which protects it from the outside world.

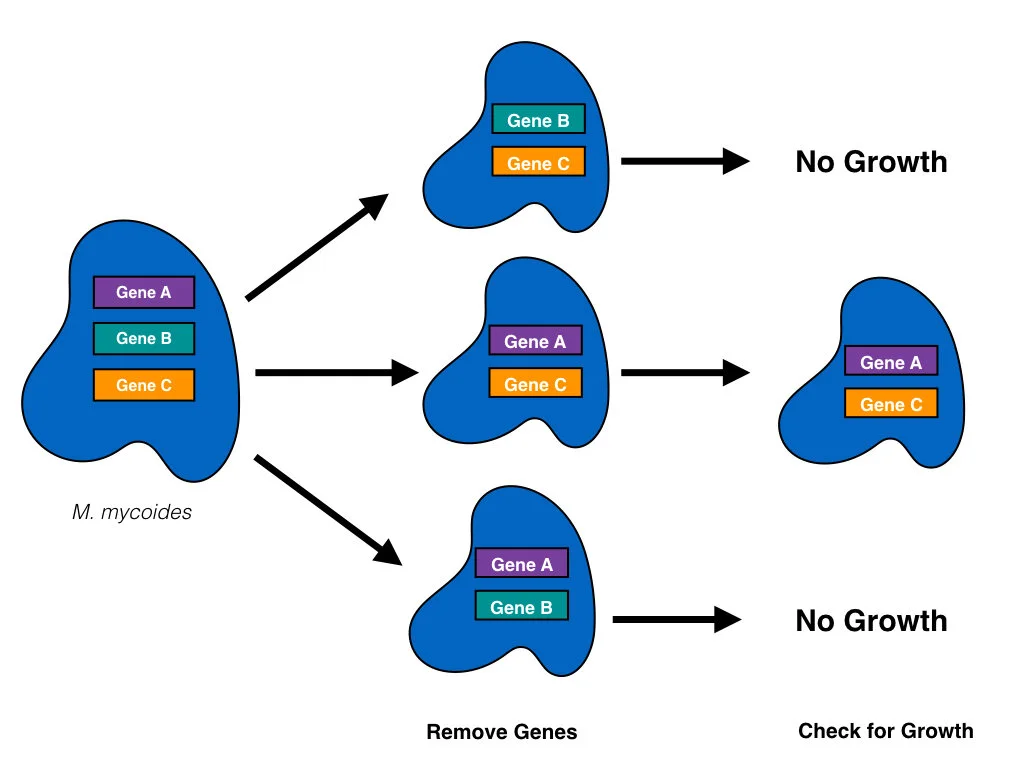

The JCVI scientists began with a bacterium, M. mycoides, which has a relatively small genome — 1 million base pairs of DNA compared to a human’s 3 billion - with the goal of developing a "minimal bacterium". Once the scientists picked which bacterium to study, they had to develop the tools to remove different parts. They called on one of humanity’s oldest friends (44% of our genome is made up of them), the transposable element, also called the transposon. Transposons are frequently called jumping genes because of their tendency to jump around in the genome of an organism. Inserting a transposon into a gene in essence inactivates that gene. The scientists cleverly used this strategy to insert transposons into every gene in the M. mycoides genome. They then grew up the bacteria and sequenced — or read the genome — to see which genes had transposons inserted in them. If a transposon inactivated an essential gene, the bacteria would die whereas if the gene were non-essential, the bacteria would live and multiply.

In this way, JCVI scientists could see which genes were not essential by sequencing the genes in which the transposon is able to insert without killing the bacteria. Using that information they then synthesized a new genome combining all of the essential genes. This final minimal cell genome was just 500,000 base pairs long and made up of 473 genes! This means that over half of the starting set of genes were unnecessary for growth. This brings us one step closer to understanding how life is sustained. Of these essential genes, most were involved in processes that scientists predicted — harvesting energy, building structures, and making replicating the genome. What scientists did not expect is to find is that 17% of the genes in the minimal genome were of unknown function. This means that those genes have never before been seen in any studied organism. Many of these genes likely belong to one of the pathways that we know but have not previously been defined. Also, some biologists are very excited by the prospect that some of these genes may belong to a whole new class of functions that have gone undiscovered. Perhaps in trying to make a minimal cell these scientists have unlocked a whole new category of processes that we need to investigate to further our understanding of life.

REFERENCES

[1] Hutchison CA 3rd ,et al. (2016). Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science. 351 (6280): aad6253.