THE RNA WORLD: HOW ALL OF LIFE (MAYBE) BEGAN

HOW LIFE ON EARTH FIRST MAY HAVE BEGUN, THROUGH THE EVOLUTION OF SELF-SUFFICIENT RNA MOLECULES.

AN OLD PARADOX

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Well, before there were chickens, there were chicken-like creatures that laid eggs. And way before that, there were reptiles, fish, sea urchins, and all other sorts of egg-laying powerhouses. The case is closed on this question; eggs have been around for a really long time, and the powers of natural selection have nudged species towards the animals we know now, including the chicken.

Here is a more interesting question: what came before chickens, eggs, and everything else? We know that natural selection changes a species over time, but this does not help us learn how life began in the first place. Billions of years ago, life consisted of primitive single-cell organisms that evolved into life as we know it. But a single cell is already a mix of molecules in organized structures, in which DNA codes for RNA that codes for proteins that carry out numerous activities. This brings up an interesting question: what was the chemical precursor to these single-celled organisms? It is difficult for scientists to understand what the earth was like so long ago, but the most popular hypothesis is that RNA was the key molecule to the beginning of life.

PRIMITIVE TECHNOLOGY

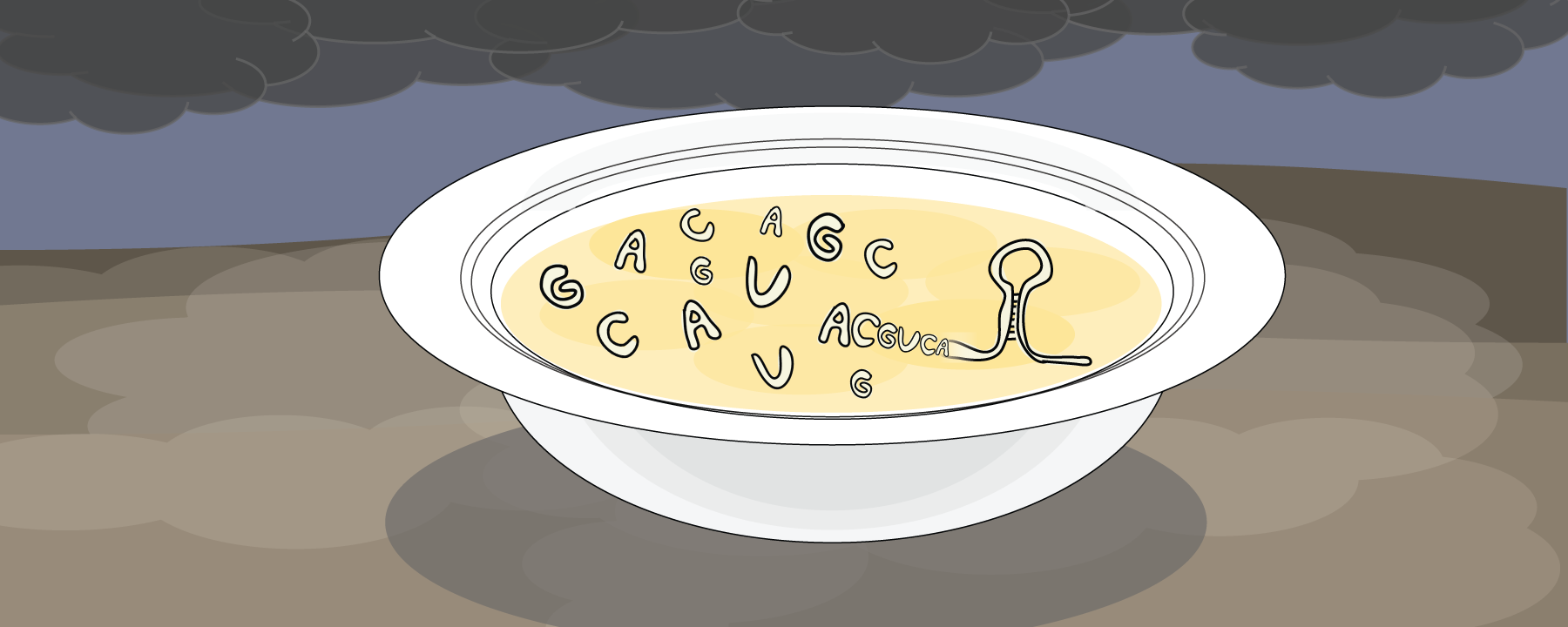

Before life existed on earth, the earth was a chemical environment that scientists refer to as the primordial soup. The high-energy molecules in this environment had the ability to form complex molecules like RNA and proteins. In the 1950s, the famous Miller-Urey experiment showed that electric discharges in the primordial soup could prompt the spontaneous formation of biological molecules such as amino acids, carbohydrates, and nucleotides1. These building blocks were important precursors to establishing a system of life that would be able to duplicate itself. However, two critical pieces of the puzzle are missing: genetic inheritance (passing genetic material from parent to offspring) and enzyme catalysis (proteins that help with chemical reactions).

The first barrier, genetic inheritance, is key to establishing a species that is able to survive just like its previous generations. When a primitive cell divides into two offspring cells, they both need to receive a copy of their parent’s genome in order to survive. In species we think of today, the genome is encoded by DNA, and a new organism gets half of its genome from each of its parents. In present-day bacteria, as well as in primitive cells, it suffices for an organism to duplicate its genome and then divide into two cells that each receive one of the copies. The question remains: how did primitive life first develop this ability?

The second fundamental barrier is the ability to catalyze chemical reactions. Present-day cells duplicate their genome using a series of enzymes, which are proteins that “catalyze” or aid chemical reactions. These enzymes (e.g. helicases, primases, polymerases, and ligases) efficiently and faithfully duplicate DNA in dividing cells. Similarly, primitive cells likely used enzymes to carry out these actions. However, a perplexing question arises: how did the first enzymes arise? All life that we know of uses enzymes to duplicate DNA, yet it is this same DNA that provides cells with the instructions to make enzymes. It appears we have come across a new chicken and egg paradox: we need enzymes to reliably build DNA and we need DNA to encode for enzymes.

HOW IT'S MADE

Enter the RNA-world hypothesis. Usually we assume that enzymes are proteins. However, it is hypothesized that before DNA and proteins were around, there were enzymatic RNA molecules that could catalyze the creation of new RNA molecules. In theory, these enzymatic RNAs, called ribozymes, would be capable of catalyzing the formation of an RNA strand that is the exact same sequence as itself. Indeed there are a number of modern day ribozymes that perform critical tasks2. Under the RNA-world hypothesis, the perpetuation of complex molecules began with the appearance of functional RNAs that were capable of their own duplication.

Furthermore, RNA consists of nucleotide bases – A, C, G, and U – much like DNA, which uses A, C, G, and T. Therefore, primitive RNA would also be able to encode genetic information in its sequence – the other major barrier to life. These first genomes would be very small; in fact, the first genomes probably only contained the sequence of a ribozyme that could catalyze the creation of a copy of itself. However, this accomplishment is paramount to the beginning of life. Once these molecules existed, natural selection could begin to nudge them towards more complex sequences, with more efficient ribozyme sequences outcompeting less efficient ones.

Over time, these complex RNA sequences could have made use of amino acids floating in the primordial soup. Eventually they could form them into polypeptides that would enhance the catalytic ability and diversity of RNA. Among these innovations would be the ribosome, an RNA/protein complex that is responsible for synthesizing proteins in present-day cells. These early biomolecules would also begin to localize with phospholipids (also present in the primordial soup), which are long hydrophobic molecules that self-assemble to form compartments. These compartments would serve to enclose and concentrate RNA and peptide components, and would eventually become the basis for the cell membrane that comprises the outer surface of cells. Finally, DNA would arise from RNA. DNA is relatively more resilient to damage from spontaneous chemical reactions, so DNA would ultimately become the final keeper of genetic information. With DNA encoding the genome, and enzymes to replicate it, ribozymes would be slowly replaced by proteins, leading to their scarcity in present-day cells.

And that is how it all began! Or could have. Electrical discharges in the earth’s atmosphere helped form ribonucleotides and other energy-rich molecules in the primordial soup. These ribonucleotides polymerized into RNA molecules with catalytic capability. Then, natural selection gave rise to more complex RNA with diverse abilities and larger genomes. These RNA molecules eventually built proteins from amino acids, bound themselves in cells made of phospholipids, and outsourced their genomes to the more stable DNA. Finally, after a couple of complex cellular advances (processes like endosymbiosis, multicellular assembly, and sex differentiation) over billions of years, we have the humans, plants, and egg-laying chickens we see around us now.

Of course, life began a long time ago, which makes it difficult to tell what happened for sure. The RNA-world hypothesis has the greatest amount of evidence, but there are lines of argument that lead to alternate origins3. We may never know the exact story of how life first came about, but I for one am relieved that it did.

FURTHER READING

REFERENCES

[1]: Science. 1953 May 15;117(3046):528-9.