HELLO MICROBE MY OLD FRIEND: HOW A DIVERSE MICROBIOME TRAINS THE IMMUNE SYSTEM AGAINST ALLERGIES

MICROBES: HOW EXPOSURE TO THE RIGHT ONES CAN BE BE A GOOD THING

Allergies, asthma and autoimmune disorders are disorders where a patient’s immune system violently reacts against something in the environment that for most people is harmless – for example peanuts and pollen in allergies, and insulin in diabetes. The immune system mistakenly considers the environmental object a threat. Why this happens in some but not all people is not understood. What is even more confusing, is that the amount of people with these disorders has risen since the 1950’s, especially in developed countries. In order to find a cure, scientists have been studying how changes in lifestyle over the past decades could have contributed to the rise of allergic disorders.

THE "HYGIENE HYPOTHESIS"

David Strachan, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, observed in 1989 that infants born in families with many siblings are statistically less likely to develop eczema and hay fever later in life. He proposed an explanation: allergic diseases were prevented by childhood infections, which infants got from interacting with their older siblings. Strachan then hypothesized that decreases in family size, improved sanitation and higher personal standards of hygiene over the past century had decreased the rate of childhood infections, which accidentally caused a widespread rise in allergic diseases. The idea of the “hygiene hypothesis” caught on in the media and the scientific community, and it quickly expanded beyond family size to include other modern hygienic lifestyle changes, such as increased use of antibiotics. Studies in the 90’s into the immunological mechanisms behind infections and allergy and asthma even provided a molecular mechanism. Bacterial and viral infections activate special immune cells called Th1 cells, whereas allergic disorders activate so-called Th2 cells. Th1 cells suppress Th2 cells and vice versa; therefore, Th1 cells induced by infections could inhibit allergy-inducing Th2 cells. On the other hand, a lack or decrease in childhood infections could allow rampant Th2 cells to cause allergies (1). However, further studies pointed out several issues with this model of cell suppression. It was discovered that infections with helminths, a type of parasitic worm, provide protection against allergic disease, even though helminths induce a strong Th2 cell response. The correlation between the decline of infections and the rise of autoimmune disorders also proved confusing, as both infections and autoimmunity are characterized by Th1 responses. Finally, it became increasingly clear that many disease-causing microbes, especially respiratory viruses such as measles and rubella, were not protective against allergic diseases and sometimes even increased a child’s chances of developing allergies later in life (2).

THE "OLD FRIENDS" THEORY

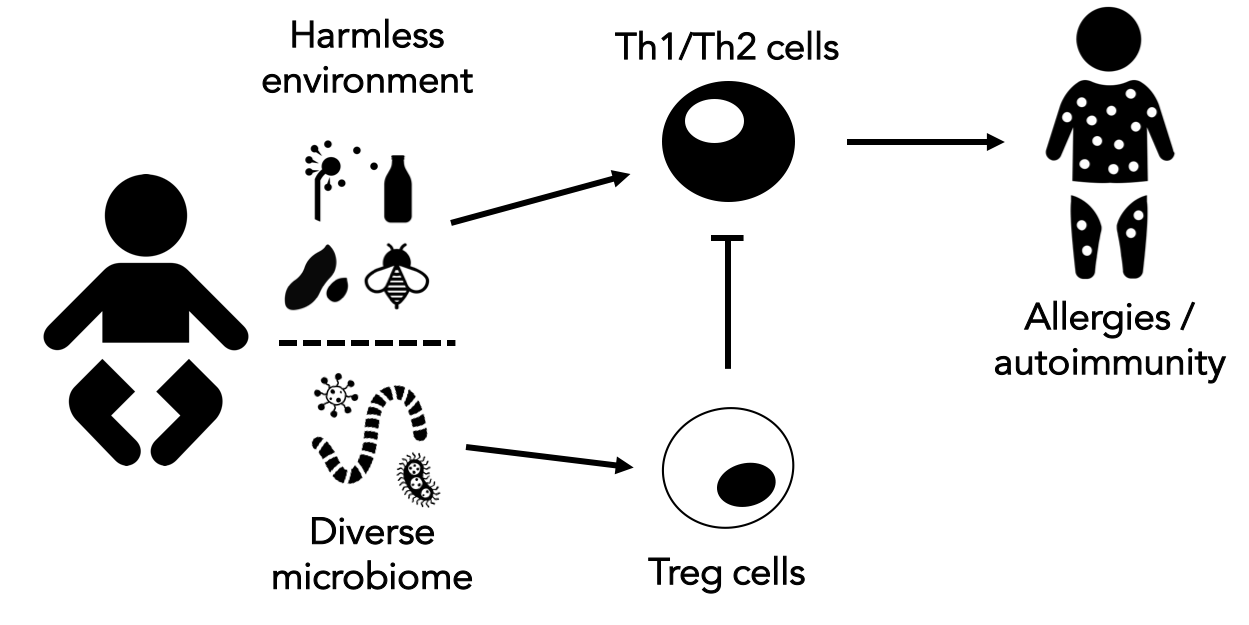

Building on the large amount of data generated in the 90’s, a new theory that refined the hygiene hypothesis was proposed in 2003 by Graham Rook, a professor of medical microbiology in University College London. His “old friends” theory argued that it was not disease-causing microbes that protect infants against allergic disorders, but early and regular exposure to non-harmful microorganisms from the environment and the human gut and skin. Rook thought that these harmless species were common during human evolution, and they taught the early immune system the difference between a threat and something that can be ignored. Tolerance to harmless microbes is often induced through another type of immune cell, called regulatory T cells (Treg). Treg cells are immune cells that inhibit inflammatory responses, including those caused by Th1 and Th2 cells. In other words, Tregs are like drill sergeants who teach soldiers like Th1 and Th2 cells when to shoot and when to stand down. Rook argued that reduced exposure to “old friends” early in life leads to fewer Treg cells, and an immune system that is more likely to react violently – be ‘trigger-happy’ - to harmless things that cause allergic disorders. One such “old friend” could be helminths, as long-lasting infection with helminths is known to activate Treg cells (3).

THE MICROBIOME AND ALLERGIC DISORDERS

Rook’s theory was expanded by other scientists to include the idea that the more harmless microbes you are exposed to, the more signals your immune system is trained to tolerate – which would suggest that a diverse microbiome protects against allergy and asthma. This seems most important during infancy, when your Th1 and Th2 soldiers of the immune system are being instructed by the Treg drill sergeants. Since 2003, there have been many animal and human studies that indeed show a positive correlation between a diverse gut and skin microbiome and protection against allergic disorders (2). But how would infants in developed countries have become less exposed to diverse microbes over the last few decades? It could be that the same improvements in sanitation and clean food and water that protect us against dangerous diseases have accidentally reduced the variety of microbes we are exposed to early in life. An infant’s earliest exposure to microbes comes from its mother during pregnancy and delivery through the vaginal canal, and from interaction with its siblings. But antibiotic usage (which kills both good and bad microbes) during pregnancy and youth has gone up, as has the rate of ‘sterile’ Cesarean section deliveries. And as Strachan already noticed, family size – and as a result, microbial diversity among siblings – has decreased. The environment plays a role as well. Children in developed countries and urban areas are less exposed to animals, tend to spend less time playing outside and have less exposure to outdoor living, which are all great sources of microbial diversity. Growing up on a farm or with a pet have both been shown to reduce the risk of developing allergic disorders later in life. Finally, a fiber-rich diet, uncommon in Western countries, can also protect the gut microbiome diversity (4).

CONCLUSION

While there are still a lot of questions about the importance of microbial diversity and allergic diseases – what role does individual genetics play, and why is it important that exposure happens during infancy? – it seems clear that some microbes can be friends that protect us from allergic and autoimmune disorders by training Treg cells. What do we do with that information? Despite what the term “hygiene hypothesis” suggests, cutting back on your personal hygiene standards will probably not help. Several studies tracked whether changes in household or personal hygiene activities impacted the incidence of asthma and allergy in infants, but they found no direct association (5). In fact, slacking on personal hygiene can increase the risk for dangerous infections. Rather than allowing dangerous pathogens into our infants’ lives, perhaps we should work to identify the microbes that can be our friends and then reintroduce them to those who suffer from allergies and autoimmune diseases. There are already studies investigating the effect of Treg-inducing helminths in patients with autoimmune disorders, and other trials looking at the effect of probiotics in allergic disorders. So far, they have generated mixed results in their ability to alleviate symptoms. Therefore, it might be more rewarding to identify the specific regulatory pathways that train the immune system, and when in life they take place (6). What to do in the meantime? Maybe take a kid to the petting zoo and let them play with some animals. In the worst-case scenario, the kid has a great day. Just don’t forget to wash their hands afterwards.

REFERENCES

Cover image: “kid petting sheep” by Mallory Simon, licensed under CC BY 2.0 Schematic made from images created by Bakunetsu Kaito, Maxim Kulikov, Delwar Hossain, Dennis Tiensvold, Julia Söderberg and The Eye from the Noun Project.

- D. P. Strachan, Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the "hygiene hypothesis". Thorax. 55 Suppl 1, S2–10 (2000).

- C. Brooks, N. Pearce, J. Douwes, The hygiene hypothesis in allergy and asthma. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 13, 70–77 (2013).

- G. A. W. Rook, R. Martinelli, L. R. Brunet, Innate immune responses to mycobacteria and the downregulation of atopic responses. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 3, 337–342 (2003).

- S. F. Bloomfield et al., Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: new perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene. Perspectives in Public Health. 136, 213–224 (2016).

- A. H. Liu, Revisiting the hygiene hypothesis for allergy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 860–865 (2015).

- M. Scudellari, News Feature: Cleaning up the hygiene hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1433–1436 (2017).