GOING WITH THE FLOW

VISUALIZATION OF UNDERWATER VORTICES REVEALS HOW FISH MAKE THE BEST OF A SWIRILNG SITUATION

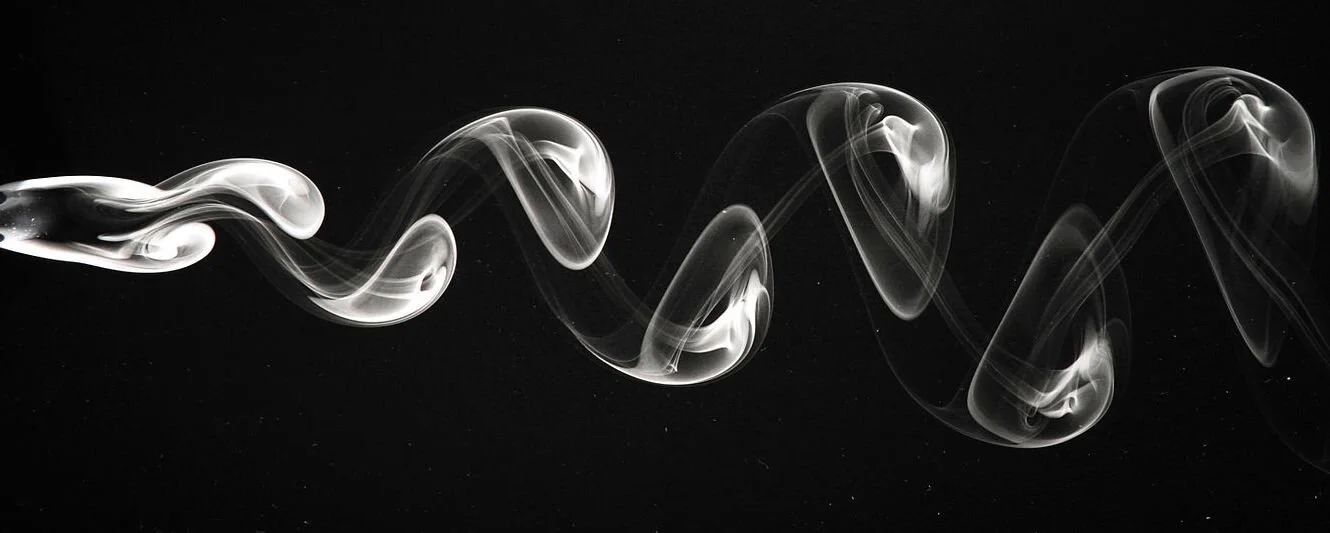

The first vortices that we often think of are destructive swirling forces of nature large enough to swallow a ship. However, they're frequently only a few inches in size, like these alternating vortices produced in the laboratory. Image by Jürgen Wagner accessed through Wikimedia Commons.

Marine animals face a lot of potential issues when swimming through the water. One wrong turn, and you could end up as someone else’s next meal. Not turning enough could result in bumping into a lot of things. But there is one important feature found everywhere that they have to face almost all the time, and this feature is rarely seen – vortices.

Vortices can be found swirling around in any fluid, be it air or water. The first examples that come to mind are usually large and destructive, like tornadoes, hurricanes, and whirlpools. However, the vortices that fishes and other swimmers encounter in the ocean are usually much more small and mundane, no more than several inches in diameter. Although these vortices are common, we’ve just begun to understand how they impact fish swimming, mainly because vortices are rarely visible. But before we spin out of control trying to understand the details of fish-vortex interactions, what are vortices and why do they matter?

WRAPPING YOUR HEAD AROUND VORTICES

In the barest terms, a vortex is the rotating motion of a bunch of particles around a common center, kind of like people running around a track. Every vortex is characterized by the term vorticity, which describes how quickly the particles in the vortex are circulating around the center. Of course, vorticity doesn’t just arise out of nowhere in a fluid at rest. There has to be a disturbance for a vortex to form.

In nature, there are many opportunities for such disturbances. Think of any river bottom populated by stones, pebbles, and boulders.

Nature is rarely uniform. All of these rocks found along the river bottom interrupt the flow of water and allow vortices to form. However, we wouldn’t know it from looking at this picture since the water and its movements are pretty much transparent. Image from Wikimedia commons.

These features act as obstacles that the water has to course around, in between, over, and under, thus breaking up the flow. As the water particles make their way by all these obstacles, some particles tumble around rock edges and swirl behind them, thus forming little vortices, as long as the water isn’t moving too rapidly. Because water is more or less transparent, these everyday vortices usually remain unseen, but underwater animals encounter them all the time as they swim around in their habitat. What would it be like to swim along with all these vortices? Would you just get thrown about into a huge mess and not be able to go where you needed to go?

VORTICES MAY LEND A HELPING HAND (OR FIN)

Turns out fish may actually be able to use vortices to their advantage when swimming. Anyone who has gone biking in a group has experienced being aided by vortices in the air when “drafting” behind other cyclists. The group’s cyclists act as the stones and pebbles in the river, and air instead of water rushes around them to create vortices. For those of us, your author included, who don’t really exercise, it’s a little less intuitive how these vortices may be helping. In order to fully explain how a fish would interact with vortices, a team of researchers from Harvard and MIT decided to examine what swimming trout would do when placed in a tank with many vortices.

The biggest challenge for work like this is actually making the flow of water visible so each vortex can actually be seen. The research team used a technique that has become very popular in this field of study called digital particle image velocimetry (DPIV). For DPIV to work, the water is seeded with thousands of tiny particles that match the density of the fluid, so they don’t float or sink. A strong light, usually a laser sheet, shines through the water to illuminate the particles. Then, you can take pictures of the particles as they move around to create detailed time-lapse footage. By measuring how far the particles move from picture to picture, it’s possible to calculate their velocities, which includes their speed and direction of movement. So, we can finally see what the water is doing! Lucky for us, when flows are revealed, they usually have some interesting secrets to share.

In the tank, the research team generated two lines of alternating vortices that would flow past either side of the trout. Of course, vortices encountered by fish in nature would never be this neat and orderly, but scientists take great care to keep conditions controlled in lab experiments.

Looking down from above in this animation of flow getting interrupted by a post on the left, we see alternating vortices forming, indicated by the two different colors. Animation by Cesareo de la Rosa Siqueira. Accessed through Wikimedia commons.

Once the flow was illuminated, researchers saw a behavior that had not been described before. Trout slalomed between vortices much like how downhill skiers weave their way around obstacles down a slope.

See this video on trouts. Slaloming between the alternating blue and orange vortices, the trout is able to use the rotation of the vortices, much like how downhill skiers weave their way around obstacles down a slopwe.

Trout swim by beating their tails, and the researchers saw the trout matching its tail beating with the oncoming vortices. What’s more, the team found trout used less muscle when swimming between vortices compared to trout swimming in still water. So it’s possible that trout are actually perserving energy by taking advantage of passing vortices. These vortices have already begun moving water in the way the tail would have beaten anyway, so trout, like cyclists in the middle of a peloton, might as well save some energy and go with the flow.

WHY DO VORTICES MATTER?

Vortices can come in almost any size and at any place, but what is their purpose? Due to its continual motion and circulation of particles, a vortex is great at transferring things – not just particles themselves, but the energy that each particle holds. And we’ve seen how the trout can harness this energy transferred from vortices to help with swimming. In fact, knowing how fish interact with the predictable, controlled vortices we’ve talked about gives scientists a foundation for future work ranging from understanding fish schooling to developing underwater vehicles. Animals are amazingly adapted to thriving in their dynamic habitats and using their surroundings to their advantage when they can. And as we keep observing nature, even phenomena that have previously remained hidden, like vortices and their interactions with swimmers, will become revealed.