Botox and Botulism: Same Toxin, Very Different Outcomes

The toxin that causes botulism, and is banned by the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, is the same toxin that people inject into their bodies for cosmetic and clinical purposes (1). Approximately seven million Americans get Botox injections each year (2). Botulinum toxin, the primary ingredient of Botox, is made by a bacterium called Clostridium botulinum. This microbe is found in plants, soil, and occasionally (but hopefully not) canned food. Botulinum toxin is one of the most dangerous biological agents of all time—making it banned by the 1972 United Nations’ Biological Weapons Convention and classified as a category A agent by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (3). Category A agents are deemed the highest risk to national security. Even knowing the dangers of botulinum toxin, it was approved for medical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1989, and for cosmetic use in 2002 (4). If this toxin is so dangerous, why are we injecting it into our bodies? And, more importantly, why are people not dying from Botox injections? The answer comes down to dose, location, and decades of careful medical research.

Botulism

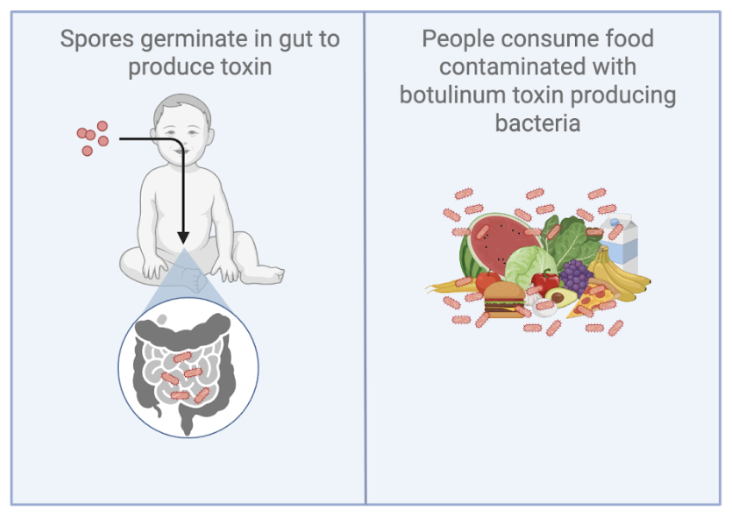

Figure 1: Common ways people get botulism. (LEFT) Bacterial spores—small, non-reproducing bacterial structures—germinate in the gut after being ingested and the microbes produce botulinum toxin. More common in babies. (RIGHT) Ingestion of botulinum toxin in contaminated foods (usually improperly canned food). This is more common in adults.

The deadliness of botulinum toxin is linked to it being the causative agent of botulism. Botulism is a rare, but serious, illness that attacks your body’s nervous system. Approximately 200 people get botulism each year in the United States. Botulism standardly occurs through one of two mechanisms: (1) bacterial spores—small, non-reproducing bacterial structures—germinate in the gut after being ingested and the microbes produce botulinum toxin, and (2) ingestion of botulinum toxin in contaminated foods (Fig.1). The first instance is more rare in adulthood, but is common during infancy5. This is due to the developing infant gut not being able to control the germination and growth of Clostridium botulinum. It is common knowledge among parents that babies cannot have honey, and this is because of the risk of ingesting the bacterial spores, which would in turn increase their risk of botulism. The second case is more common in adulthood, and comes from contaminated canned foods. Since this case refers to the direct ingestion of botulinum toxin, the incidence of botulism is more rapid. This toxin is extremely dangerous, yet people receive injections of it frequently.

Botulinum toxin in the body

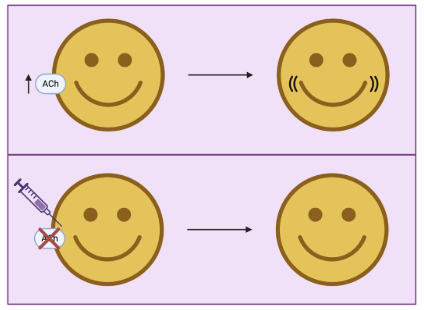

Figure 2: Acetylcholine is released during the activation of the neuromuscular junction. The continued production of acetylcholine is associated with the appearance of fine lines. Injection of Botox interrupts the release of acetylcholine.

In order to understand Botox, it’s useful to understand how it interacts with our bodies. When a person smiles, a signal from the brain activates muscles in the mouth to cause the lips to upturn. The process of smiling occurs through something called the “neuromuscular junction,” which is the place where the brain meets muscles. Acetylcholine is one of the signals involved in the neuromuscular junction. Specifically, acetylcholine is known for its role in causing muscles to contract. When we smile, acetylcholine is released. Repeatedly smiling will eventually lead to fine lines and wrinkles caused by constant muscle contraction. Some people might decide that they don’t like the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, so they will seek out Botox treatments. Botox removes these markings by blocking the release of acetylcholine (Fig. 2). This leads to a paralysis of the muscles wherever the Botox was injected. Botox permanently blocks acetylcholine release in the affected nerve endings, but its effects wear off because the body naturally forms new nerve connections over time (6,7). The blocking of acetylcholine temporarily leads to the favorable effects of smooth skin and no wrinkles, but this is also the same way that botulism works. So why is botulism deadly, but Botox is safe?

Origins and evolution of Botox uses

While many of us know Botox as a cosmetic treatment, it originated as a medical treatment, called Oculinum. As the name Oculinum might suggest, it was designed for treating problems in the eyes (8). In particular, botulinum toxin is used to treat strabismus, an eye condition where there is a muscular defect in people’s ability to move their eyes properly. In the 1990s, muscular surgery in the eye was the main form of treatment for strabismus, but it was a flawed surgical procedure that often required another operation later on. Ophthalmologist, Dr. Alan Scott, was looking for alternative ways to weaken the muscles around the eyes. At this point, scientists understood that low doses of botulinum toxin A paralyzes muscle locally where it is injected. Dr. Scott was curious if this would also work in the context of strabismus. Through the use of various animal models, he found this was a potent and effective solution for strabismus, and perhaps even other conditions caused by overactive muscles (8,9). Today, there are continued medical uses of Botox. It is still used to treat conditions of the eye with overactive muscles, but also for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder that causes dysfunction of the jaw and surrounding muscles, among others. While Botox was initially a medicinal treatment, it has expanded to what we more commonly think of, which is in the context of cosmetics. People get Botox to give the appearance of smoothed skin and reduced wrinkles. All the places someone might get visible wrinkles—around the eyes, the forehead, around the mouth—are common Botox injection sites.

Safety of Botox injections

The main reason Botox doesn’t lead to botulism primarily has to do with dosing. Botox is an extremely diluted botulinum toxin. A lethal dose of botulinum toxin for a 150 pound individual is 70 nanograms, which is similar in weight to a single dust particle. Botox injectables typically contain about 0.05 nanograms of botulinum toxin (4). To put this in perspective, the amount of toxin used in a cosmetic Botox injection is thousands of times lower than the amount associated with systemic toxicity. This diluted dose is high enough to create the desired cosmetic or medical effects, but low enough to not cause systemic harm to the body. The other difference between injectable Botox and botulism is the site-specific nature. When botulism occurs, it is a high dose that is likely affecting multiple areas of the body. However, in Botox injections, a person receives a low dose to a very specific area, which reduces the potential of systemic effects in the body. While botulism and Botox injections undergo the same processes in the body, their effects are very different. The dosing and site-specific nature of Botox injections makes it so Botox isn’t lethal.

Conclusion

In science, we often encounter tools that can be dangerous in one context and lifesaving in another. We call this dual-use research. Botulinum toxin is a prime example of a dual-use material. While botulinum toxin could cause catastrophe, medical-grade injectable Botox is not just safe, but also has the potential to treat discomfort from TMJ, migraines, and more.

References

1. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon. EBSCO https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/chemistry/botulinum-toxin-biological-weapon.

2. ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery. 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/news/statistics/2018/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2018.pdf (2018).

3. CDC High-Priority Biological Agents and Toxins*. Merck Manual Consumer Version https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/multimedia/table/cdc-high-priority-biological-agents-and-toxins.

4. Nigam, P. K. & Nigam, A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J. Dermatol. 55, 8–14 (2010).

5. CDC. National Botulism Surveillance Summary, 2021. Botulism https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/php/national-botulism-surveillance/2021.html (2025).

6. Wheeler, A. & Smith, H. S. Botulinum toxins: mechanisms of action, antinociception and clinical applications. Toxicology 306, 124–146 (2013).

7. Sellin, L. C. The pharmacological mechanism of botulism. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 6, 80–82 (1985).

8. Osako, M. & Keltner, J. L. Botulinum A toxin (Oculinum®) in ophthalmology. Surv. Ophthalmol. 36, 28–46 (1991).

9. Scott, A. B. Botulinum toxin injection of eye muscles to correct strabismus. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 79, 734–770 (1981).