Composting: On Campus and Beyond

You have just finished a hearty meal, scraping the last remnants out of a plastic container. You might be tempted to save the container and use it to store leftovers in the future, but the plastic looks too soiled to recover after washing. Would it make sense to put this container into the compost bin?

You think back to the other food containers you’ve seen, some of which were made of “compostable” materials. Perhaps these packages break down into the soil, leading to a more sustainable meal. This makes you wonder: what makes a package (especially food packages) compostable, and how does the commercial composting process work?

What is composting?

Composting is a familiar word for gardeners, who have long used food and table scraps to add nutritional value to the soil. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines this process as the “managed, oxygen-required biological decomposition of organic materials by microorganisms” [1]. Organic materials may include natural substances such as plant or animal tissues.

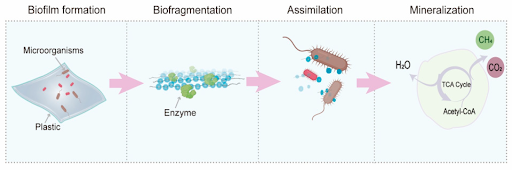

Microorganisms can break down, or biodegrade, organic materials because they produce specific enzymes. These enzymes are proteins that can catalyze the reactions needed to disassemble plant or animal products.

Figure 1 (above). The process of microbial depolymerization and degradation. In the first phase, microorganisms with plastic degrading abilities attach to the material’s surface to form sheets, or biofilms. Then, the organisms produce enzymes to break down the materials into smaller units, or monomers (described further below). The microorganisms can then use (or “assimilate”) the broken down material in their own metabolism, making products such as methane and carbon dioxide (“mineralization”). Image and description summarized from Lu, Li, Zhao and Shao, 2024.

The end product of the biological decomposition process are nutrients that build soil health and provide nutrients to plants [1]. Traditional compostable materials include food scraps and leaves [1]. But how can compostable materials replace materials such as the petroleum-based plastic in food containers?

How are compostable plastics different from petroleum plastics?

Compostable plastics have been developed to break down when microorganisms digest the material [2]. In comparison, traditional, petroleum-based plastics undergo a very slow degradation that ultimately leads to an increase in plastics and microplastics in the environment [3]. Traditional plastics cannot be composted [3].

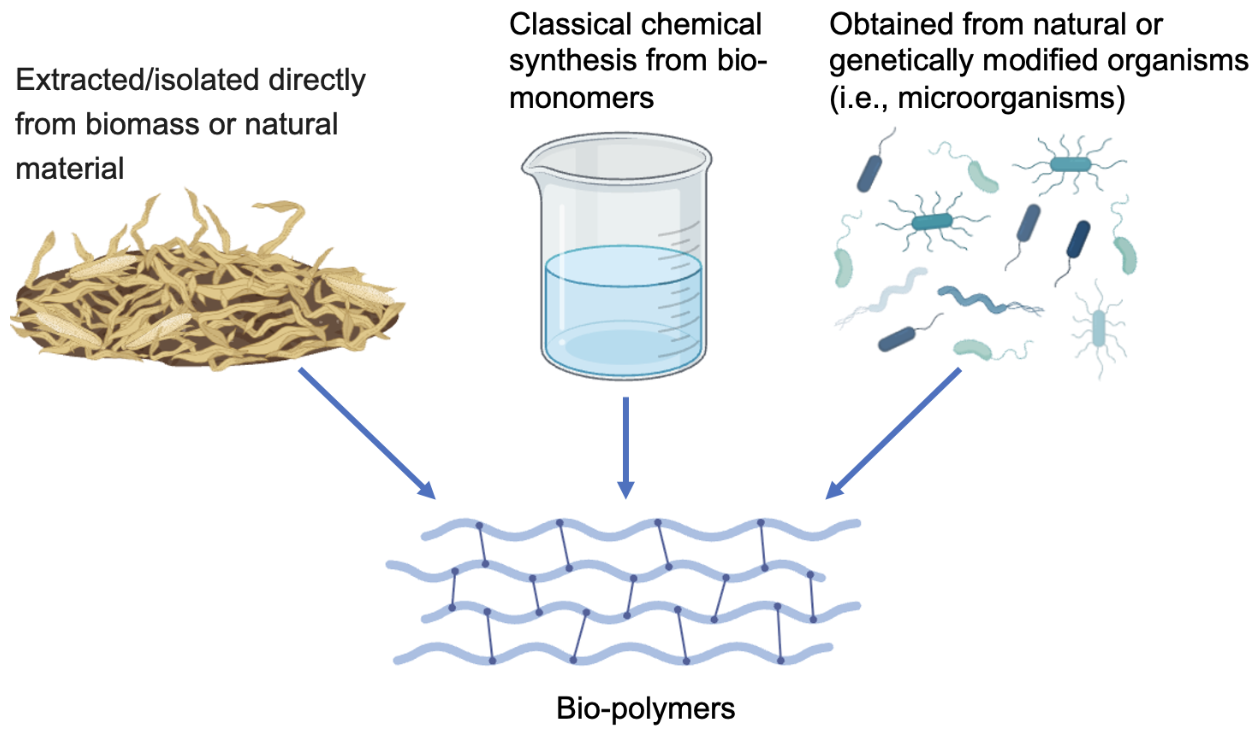

Compostable plastics are made up of natural units called bio-polymers. These units may be sourced naturally (i.e. from starch in plants such as sugar cane or corn), chemically synthesized from natural building blocks, or produced by microorganisms [3].

Figure 2. Adapted from Shaikh, Yaqoob, and Aggarwal, 2021. Made using BioRender.

Over time and under the right set of conditions, packages made from these materials will break down into air, water and soil, preventing waste accumulation and harm to natural ecosystems [3].

Compostable cornstarch-based containers used for your food from on-campus restaurants such as Kali Greek Kitchen can be degraded within six months through industrial composting, as compared to plastic containers which may take hundreds of years to decompose [4].

“Microbes do the work in composting - polylactic acid (PLA) [commonly made from corn starch] and fiber [paper or sugar cane]-based compostable materials can be broken down by microbes,” says Julie Muir, Associate Director of Zero Waste Systems at Stanford University’s Office of Sustainability, who is working to reduce waste and divert campus waste away from the landfill.

What makes something compostable?

Packaging and single-use products are not always compostable. For example, in California, compostable products must meet certain standards. For example, these products must be labeled in a manner that distinguishes them from noncompostable products and have a total organic fluorine concentration of less than 100 parts per million [5]. One example of a third-party certifier is Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), which has specific guidelines for their compostable certification [5].

Containers and packaging are compostable on campus if it has the label “compostable” on it, explains Muir. This label signifies that the product breaks down according to the BPI standards in a commercial composting facility. On the other hand, “bio-degradable” labels on products do not necessarily signify anything, Muir says.

“Almost everything can biodegrade over time, but certified compostable products will break down in a commercial compost facility within a specific period of time” she says.

Similarly, according to the World Wildlife Fund, “biodegradable plastic is defined by its ability to break down completely into substances found in nature…this sounds good in theory, but in practice, doesn’t often work.”

Compostable plastic also biodegrades, but it is specifically designed and tested to be processed either in commercial composting facilities [2]. Composting facilities use specific conditions to ensure that the material breaks down into usable soil nutrients [2].

Accordingly, one BPI eligibility requirement is that a compostable item “must be associated with desirable organic wastes, like food scraps and yard trimmings, that are collected for composting,” and the item should not require disassembly to be composted [6]. Specifically, BPI can certify products under the ASTM D6400 and ASTM D6868 guidelines [6].

ASTM D6400, published by the American Society for Testing and Materials, includes a requirement that the material breaks down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass at a rate similar to natural compostable materials like yard trimmings [7].

Muir noted that the results from a recent campus waste characterization, or audit, revealed that 40% of campus waste placed into landfill bins is compostable. Therefore, it is important that students and community members place their compostable waste in the green labeled bins found around campus.

“When it comes to waste, if every individual paused for a few seconds to figure out the correct bin to put their waste in, we’d have such a great impact and closer to our diversion goal.,” she says.

How does commercial composting work?

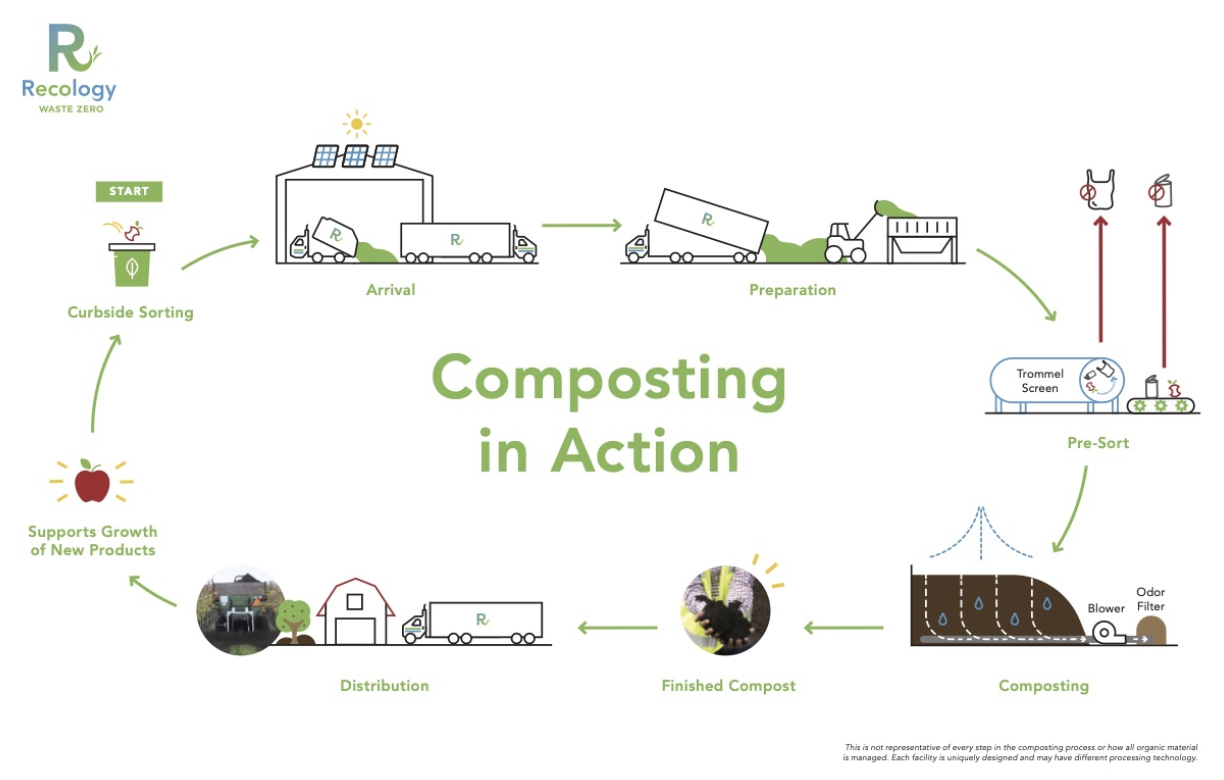

The process of commercial composting required to break down compostable materials is notably different from backyard composting. Large scale composting can be achieved by larger-scale compost collection and commercial processes like in-vessel composting [8].

Organic materials are often shredded and mixed, and then deposited in a device/vessel that controls temperatures, hydration, and aeration [8]. Then, the device sterilizes the compost with high temperature to remove any harmful bacteria [8].

Muir describes the multi-step process that waste in a compost bin on campus undergoes after being transported to a commercial compost facility. First, the facility may sort out any larger pieces of garbage present in the compost load. Unfortunately, they cannot sort out smaller items like petroleum-based plastics or other contamination.

Facility staff then use a chipper to decrease the size of the waste items and give microbes more surface area to break down the compost. The material is put into large aerated piles that have continuous airflow through pipes at the bottom of the pile, creating an environment for microbes to break down the compostable material [9].

The composting facility then screens the remaining waste to ensure that it is generally a uniform smaller size - larger leftovers may have to be sent to the landfill.

Figure 3. Composting in Action, from Recology.

We have to reduce the amount of petroleum-based plastics in the compost bin because these types of plastics cannot be broken down by microbes, Muir says. Even now, certain products may have both compostable and non-compostable components. For example, some typical fiber-based coffee cups may have a petroleum based plastic inside liner to prevent the cup from dissolving when liquid is added. Thus, there are efforts to ensure that only compostable-plastic lined cups are used.

What can we do to improve composting?

Muir suggests that individuals take a “responsible risk on recycling”, as many recycling plants have waste sorting capabilities. However, Muir says to “be cautious with composting”. Many composting facilities cannot process petroleum-based plastics, so it is harmful when recyclable materials are accidentally included in the compost.

Furthermore, the Office of Sustainability has established a few helpful resources to help community members better sort their waste. They have created a Waste Wise Guide at sustainable.stanford.edu, launched this past April. The search tool provides guidance about where to put certain items (such as plastic takeout containers, bike helmets, and coffee filters), and even includes answers to sorting typical lab and cafe items.

Additionally, the Office of Sustainability has a Waste Sorting Training Video which is under 10 minutes and offers a great overview of how to sort waste on campus and beyond.

There are also initiatives for more items on campus to be reusable. While compostable materials are a good choice for single-use items, the best choice is to move towards reusable products, Muir says. Muir and her team are hoping to continue reducing waste by, for example, encouraging the adoption of reusable food containers.

Thank you to Julie Muir and the Stanford Office of Sustainability!

References

EPA. (2018, October 16). Composting at home. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/recycle/composting-home

World Wildlife Fund. (2022, April 8). Is biodegradable and compostable plastic good for the environment? Not necessarily. World Wildlife Fund. https://www.worldwildlife.org/blogs/sustainability-works/posts/is-biodegradable-and-compostable-plastic-good-for-the-environment-not-necessarily

Shaikh, S., Yaqoob, M., & Aggarwal, P. (2021). An overview of biodegradable packaging in food industry. Current Research in Food Science, 4(1), 503–520. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.07.005

Reduce Waste with Compostable Products | World Centric. (2025). World Centric. https://www.worldcentric.com/impact/sustainability/about-our-products/

Truth-in-Labeling Laws: Protecting California Consumers from False Marketing Claims. CalRecycle. https://calrecycle.ca.gov/plastics/labeling/

Eligibility for BPI Certification. (2025). BPI World. https://bpiworld.org/eligibility

What does BPI Compostable mean? (2025). Good Start Packaging. https://www.goodstartpackaging.com/what-does-bpi-compostable-mean/

US EPA. (2015, August 19). Approaches to Composting. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/approaches-composting#models

Biyada, S., Merzouki, M., Dėmčėnko, T., Vasiliauskienė, D., Ivanec-Goranina, R., Urbonavičius, J., Marčiulaitienė, E., Vasarevičius, S., & Benlemlih, M. (2021). Microbial community dynamics in the mesophilic and thermophilic phases of textile waste composting identified through next-generation sequencing. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03191-1