Nitrogen and Phosphorus: From Fossil to Fertilizer to Food

In 1865, as the American Civil War drew to a close, tensions were boiling over between Spain and its former colonies. Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia banded together to chase Spain away from the Chincha Islands, which contained something almost as valuable as gold—guano. This conflict soon became known as the Guano War [1]. Why would people fight over bird poop? To answer this question, we must dive deep into the history of fertilizer and understand how we are able to grow the food that we eat every day.

People have long understood the value of using manure to fertilize soil so that crops could have enough nutrients to grow. Although nitrogen—a vital nutrient for life—is abundantly present in the air we breathe, in order for plants (and humans) to absorb it in our bodies, it needs to be present in a bioavailable form. Guano in particular contains especially high concentrations of bioavailable nitrogen and phosphorus, and the Incas were well aware of this, carefully managing their guano reserves and even imposing the death sentence for hunting seabirds. In fact, the word guano comes from the Quechua word wanu, which means both dung and fertilizer [2].

In the 19th century, the global population was exploding, and traditional means of farming were struggling to sustain the growing population. As a result, fertilizer became increasingly valuable as a way to dramatically improve the quality and quantity of crops that could grow in a given plot of land. However, natural fertilizers, like guano, were insufficient. Only a few years after the end of the Guano War, the Chincha Islands were depleted of guano, and Peru, Chile, and Bolivia would go to war again—this time against each other, for control over caliche, a mineral rich in nitrates (a bioavailable form of nitrogen), deposits in the Atacama Desert. Chile would ultimately win the war, ensuring the relative prosperity of Chileans for years to come and redrawing borders to their current positions [3].

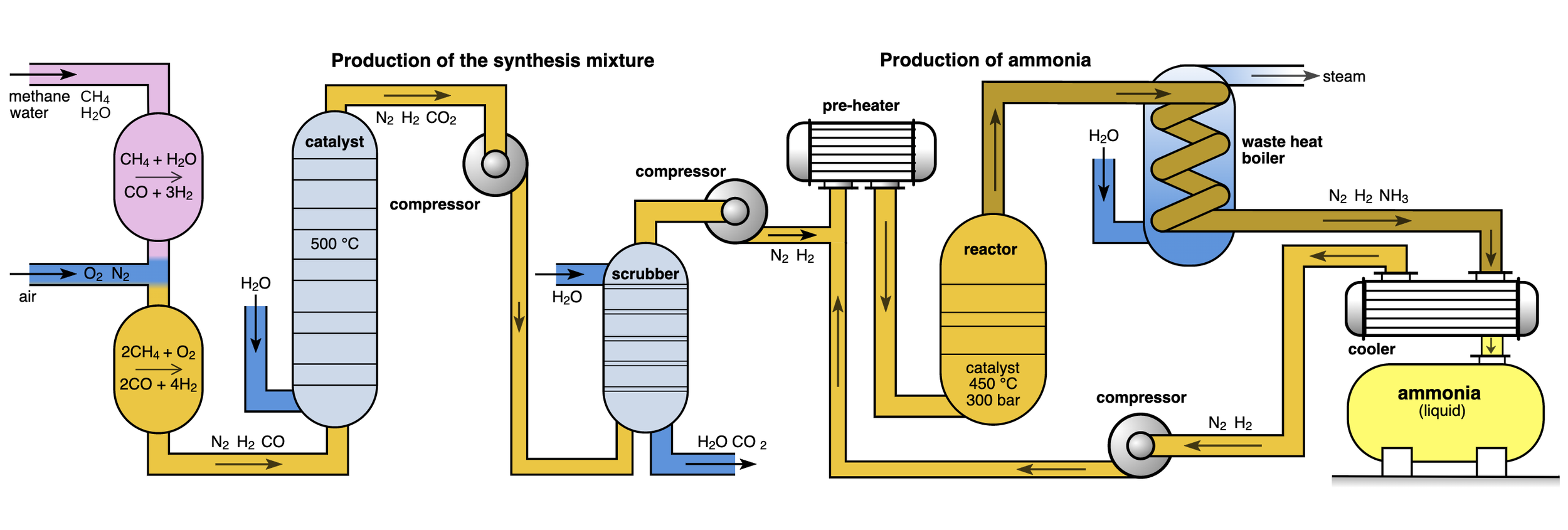

Cut off from the caliche reserves in the lead up to World War I, Germany was forced to develop a way to synthesize nitrates, which are also a key ingredient in explosives. In 1913, two ingenious scientists developed the Haber-Bosch process, an industrial chemical process that could take the nitrogen from the air and convert it into ammonia [4], and through another process into nitrates—no more fighting over bird poop! Today, over 50% of nitrogen fertilizers are produced through the Haber-Bosch process, and it’s estimated that as much as 80% of the nitrogen in your body comes from this process [5]!

Diagram of Haber-Bosch industrial process to produce ammonia for use in fertilizers - estimated that as much as 80% of the nitrogen in your body comes from this process! Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Nitrogen and phosphorus are the two most important fertilizers, because they both are crucial components of the basic building blocks of life. Both are used in the makeup of DNA and RNA, and nitrogen in particular is the key component of amino acids that make up proteins in our cells [6]. Phosphorus is essential for energy production, and along with nitrogen, is necessary for the growth, maintenance, and repair of all tissues and cells in your body [7]. Its predominant use, however, comes in the form of hydroxyapatite, a phosphate-bearing mineral that makes up around 70% of your bones and teeth [8].

Unlike nitrogen, phosphorus fertilizers still entirely come from minerals we dig up from the ground. Phosphorus is present in the earth primarily in the form of a mineral called fluorapatite, which is closely related to hydroxyapatite. In fact, most phosphorus fertilizer comes from sedimentary phosphate deposits that were formed from marine animal remains—the shells, teeth, and bones of animals who lived millions of years ago [9]. In the US, most phosphate is mined in Florida, while in Europe, it comes primarily from Morocco [10].

Three hundred million years ago, all of the land masses on Earth were united as one supercontinent called Pangea, and what is now Florida was connected to what is now Morocco. After it broke apart, both Florida and Morocco were submerged for millions of years as shallow seas where many marine animals lived and died. Today, the phosphate mines in both places regularly uncover the teeth and skeletons of animals, so much so that the phosphate-rich region in Florida is named Bone Valley (containing fossils from 5-23 million years ago) and the one in Morocco is nicknamed the “shark graveyard” (footnote 1 below) (containing fossils from 35-110 million years ago) [11-13].

Turning fossils into fertilizer into food is a long process, one that starts with digging a really, really big hole in the ground. Excavators the size of a house dig layer after layer into the ground where the phosphate rock has been identified (footnote 2 below). Typically, several meters of rock that contain very little phosphate (the overburden) need to be removed first in order to get to the phosphate rock underneath. Then, layers are excavated and trucked out of the huge pit bit by bit, and layers that contain minimal phosphate (the interburden) are discarded as waste rock [9, 14].

The valuable ore then goes through the most energy-intensive step in the process: crushing and grinding. The big rocks that are scooped up need to be ground down into tiny, micron-sized particles. Luckily, phosphate rock is relatively soft, so it doesn’t need to be ground much. The ground-up ore then goes through a series of sieves to filter out particles that are too large or too fine to make it through the next stage of the process. These are often sand or clay particles that do not contain much phosphate [9, 14].

The author on-site at a phosphate mining operation in Morocco. Photo credits to author.

The particles are then washed and turned into a slurry, which is further size-segregated via an intense spinning process. The slurry is sent to a vat in which air bubbles and soap-like chemicals work together to collect valuable minerals at the top while waste minerals sink to the bottom. The final step of the mineral processing is the chemical transformation, where the phosphate ore is treated with sulfuric acid. The final product is phosphoric acid, which can now be turned into phosphate fertilizer [9, 14]!

Over 150 years after the Guano War, where we get our nitrate and phosphate fertilizer to feed the exponentially growing population is still of utmost importance. The Haber-Bosch process and phosphate mining together ensure that there will be enough food on your plate. And they share something else in common: they are both becoming increasingly outdated in the era of climate change. The Haber-Bosch process is incredibly energy intensive, and it alone emits 500 million tons of CO2 per year (about 1-2% of global emissions) [5]. Phosphate mining not only generates vast quantities of environmentally-harmful waste, which are often either dumped in the ocean or stacked up in massive piles, but also uses large amounts of sulfuric acid, which is primarily produced as a byproduct of fossil fuel refining [9]. Thankfully, scientists are working on improving both of these processes, and hopefully, with lots of hard work, we can design and build a more sustainable future for us all.

Footnotes:

1. In fact, OCP Group, the big phosphate mining company in Morocco, has shark teeth in its logo in reference to this!

2. Technically, the process of identifying where in the ground the valuable mineral is, called mineral exploration, goes first. This can often be a lengthy and complex process of evaluation by geologists and geochemists to determine from the surface what lies beneath.

References

“Remember the Guano Wars” Breakthrough Institute, 2018. https://thebreakthrough.org/articles/remember-the-guano-wars

Cushman, Gregory T. (2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: a Global Ecological History. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139047470. ISBN 978-1-107-00413-9.

Conway, Ed. (2023). Material World: The Six Raw Materials That Shape Modern Civilization. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-593-53434-2.

Flavell-While, Claudia. “Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch – Feed the World” The Chemical Engineer, 2010. https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/features/cewctw-fritz-haber-and-carl-bosch-feed-the-world/

Boerne, Leigh Krietsch. “Industrial ammonia production emits more CO2 than any other chemical-making reaction. Chemists want to change that” Chemical & Engineering News, 2019. https://cen.acs.org/environment/green-chemistry/Industrial-ammonia-production-emits-CO2/97/i24

Smith, Allison. “Proteins” 1996. https://www.princeton.edu/~freshman/science/protein/

Cho, Renée. “Phosphorus: Essential to Life—Are We Running Out?” Columbia Climate School: State of the Planet, 2013. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2013/04/01/phosphorus-essential-to-life-are-we-running-out/

Habibah TU, Amlani DV, Brizuela M. Hydroxyapatite Dental Material. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513314/

“How phosphate is mined and processed” Carleton University. https://cdn.serc.carleton.edu/files/integrate/teaching_materials/mineral_resources/unit_6_reading_phosphorus.pdf

USGS. “Phosphate rock” 2024. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024-phosphate.pdf

OCP Group. “What is Phosphate?” https://www.ocpgroup.ma/en/what-we-do/what-phosphate

USGS. “Bone Valley” https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Geolex/UnitRefs/BoneValleyRefs_553.html

Kowinsky, Jason. “Moroccan Otodus” Fossilguy.com. https://www.fossilguy.com/topics/morocco-phosphate/index.htm

“Phosphate Flotation” 911Metallurgist, 2019. https://www.911metallurgist.com/blog/phosphate_flotation/