Venus is Back: The Molecule That Revived a Dead Planet

Figure 1. The barren environment of Venus's surface, photographed by the Venera 13 lander, which endured the planet’s extreme conditions for two hours.

Mars has taken the spotlight as humanity’s potential “next home” in the Solar System. But what about Venus, Earth’s closest planetary neighbor and twin in size? Unfortunately, that’s where the similarities end. Its thick atmosphere is laced with toxic sulfuric acid clouds, wind speeds surpass the most powerful tornadoes on Earth, and temperatures soar above 470°C (880°F), hot enough to melt lead (1). These extreme conditions have rendered Venus inhospitable to life. Even spacecraft struggle to survive on Venus. For instance, the Soviet Venera 13 lander withstood the planet’s extreme heat and pressure for only two hours before it was crushed to pieces (2) —a stark contrast to the Opportunity Rover on Mars, which operated for nearly 14 years.

Venus may be named after the goddess of love and beauty, but its environment is certainly not hospitable to life—which has ruled out the planet for decades as a candidate for habitability. That changed briefly in late 2020, when scientists studying Venus's atmosphere reported the unexpected detection of phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere (3): a chemical that is produced by living organisms on Earth. The announcement sparked widespread excitement, with some hailing the discovery as a sign of microbial life in Venus’s clouds. However, the discovery was met with skepticism and later refuted. Nonetheless, this story renewed scientific interest in Venus, prompting a fresh look at the planet’s potential to harbor life and inspiring a new wave of exploration. In this article, we’ll explore this controversial discovery and explore how a false discovery has helped pave the way for upcoming missions to re-examine our closest planetary neighbor.

From Discovery to Doubt: Phosphine on Venus

In 2020, a Nature scientific article made headlines when a team led by astrobiologist Jane Greaves examined Venus's atmosphere with the ALMA Observatory and saw that the light spectrum of Venus had a dip at a wavelength unique to phosphine4. Not only was the presence of the phosphine biomarker surprising, but also was the amount detected.

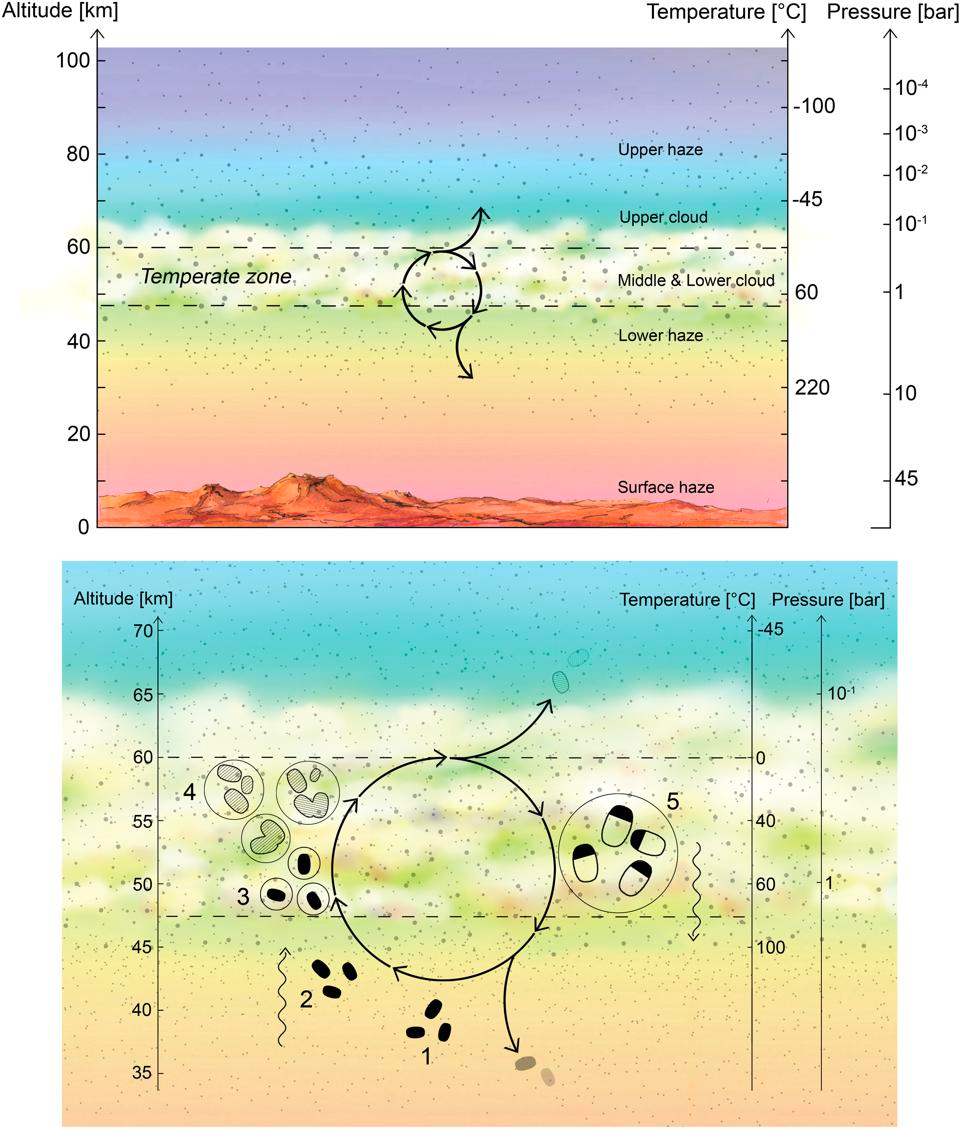

According to the Nature scientific journal in October of 2020, phosphine is unlikely to be produced at Venus's surface because it would be quickly broken down by the planet’s highly acidic atmosphere (4). This implies that the chemical must be continuously produced within the upper atmosphere of Venus—specifically, in its temperate cloud layers—raising the possibility of a potential living source, such as anaerobic, airborne microbes (5).

Figure 2. A hypothesized pathway to produce the phosphine levels discovered by Greaves, including the potential microorganisms in Venus's atmosphere in the bottom figure (6).

But this discovery soon fell into controversy. Several months later, follow-up studies revealed that the original data had been miscalibrated, and the actual phosphine levels were 20 times lower than measured (7). Today, the original Nature publication by Greaves and her team holds an editor’s note to acknowledge the processing error in the ALMA Observatory data and advise readers to interpret the results with caution (8). Since then, modern tools have continued to challenge the original findings. In 2023, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) could not find any phosphine in the upper layers of Venus's atmosphere, where it was previously detected (9).

Why the Next Decade of Space Exploration is Returning to Venus

Although the phosphine discovery was eventually refuted, it reignited scientific interest in Venus as a potential haven for life—past or present. Once considered a dead world, Venus is now being examined through new hypotheses and upcoming missions, as scientists reconsider the planet’s complex history.

Around 700 million years ago, Venus underwent a catastrophic resurfacing event, likely caused by heat building up inside the planet with no way to escape—since Venus doesn’t have moving surface plates like Earth. The built-up pressure unleashed massive volcanic eruptions that overturned 80% of the crust and boiled away carbon dioxide once trapped in its rocks (10). The sudden release of carbon dioxide trapped heat and surged the planet’s temperatures, triggering a runaway greenhouse effect that transformed Venus into the scorching world we see today.

Prior to this dramatic transformation, Venus may have been more Earth-like. Simulations from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggested that Venus could have maintained stable temperatures and liquid water before the resurfacing event (10). However, not all scientists agree. Climate models of Venus rely heavily on uncertain assumptions, such as the amount of water in the planet’s early atmosphere, the intensity of volcanic eruptions, and more. Even small variations in these inputs can lead to vastly different conclusions. In a recent 2024 study from the University of Cambridge, Tereza Constantinou and her team found that, unlike on Earth, the volcanic eruptions on Venus are “dry” and lack water (11), suggesting that the planet’s interior has never held water—undermining the theory that Venus once had oceans or a temperate Earth-like climate.

Figure 3. Artist’s impression of NASA’s DAVINCI probe descending through Venus’s thick atmosphere to capture high-resolution images of the planet’s terrain (16).

Since the debate is far from over, Venus is one of the most exciting targets for exploration in the coming decade. A new generation of missions are preparing to visit Venus for the first time in over 40 years12. NASA’s upcoming DAVINCI mission will release a spherical probe that will descend into Venus’s thick clouds, measuring its chemical makeup and capturing images with unprecedented detail13. NASA’s VERITAS mission will map the planet’s surface to reveal the planet’s volcanic history. In addition, the Rocket Lab/MIT Venus Life Finder in 2026 will be the first private mission to Venus, which aims to search for organic molecules in the planet’s clouds. Together, these missions promise to finally uncover the mysteries of Venus’s dynamic history and its present potential for habitability.

Conclusion

A single molecule—phosphine—transformed our perspective on Venus and reignited scientific curiosity about our closest planetary neighbor. As a new era of exploration begins, each mission will not only bring us closer to understanding Venus’s past, present, and future, but also the broader conditions that shape the search for life across the universe.

References

Choi, Charles Q., and Chelsea Gohd. “Venus: The Scorching Second Planet from the Sun.” Space.com, Space, 29 Sept. 2022, https://www.space.com/44-venus-second-planet-from-the-sun-brightest-planet-in-solar-system.html.

Howell, Elizabeth. “Venera 13 and the Mission to Reach Venus.” Space.com, Space, 25 Mar. 2019, https://www.space.com/18551-venera-13.html.

O'Callaghan, Jonathan. “Life on Venus? Scientists Hunt for the Truth.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 2 Oct. 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02785-5.

Greaves, Jane S., et al. “Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 14 Sept. 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-020-1174-4.

Mathewson, Samantha. “Possible Life Signs in the Clouds of Venus: Space.” EarthSky, Space, 6 May 2021, https://earthsky.org/space/phosphine-disequilibrium-venus-atmosphere-pioneer-venus-1978/.

Siegel, Ethan. “Don't Bet on Aliens: Phosphine Is Amazing, but Doesn't Mean 'Life on Venus's.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 15 Sept. 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2020/09/15/dont-bet-on-aliens-phosphine-is-amazing-but-doesnt-mean-life-on-venus/?sh=2e8235494fbc.

Atkinson, Nancy. “The Quest for Life on Venus.” The Planetary Society, The Planetary Society, https://www.planetary.org/articles/the-quest-for-life-on-venus.

Greaves, Jane S., et al. “Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 14 Sept. 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-020-1174-4.

Bandari, Anashe. “No Phosphine on Venus, According to Sofia.” NASA, NASA, 29 Nov. 2022, https://blogs.nasa.gov/sofia/2022/11/29/no-phosphine-on-venus-according-to-sofia/.

Mathewson, Samantha. “Venus May Have Supported Life Billions of Years Ago.” Space.com, Space, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.space.com/planet-venus-could-have-supported-life.html.

Collins, Sarah. “Researchers Deal a Blow to Theory That Venus Once Had Liquid Water on Its Surface.” University of Cambridge, 2 Dec. 2024, www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/researchers-deal-a-blow-to-theory-that-venus-once-had-liquid-water-on-its-surface.

Luscombe, Richard. “NASA Plans Return to Venus with Two Missions by 2030.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 2 June 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/jun/02/nasa-venus-return-two-missions.

Shekhtman, Lonnie. “DAVINCI Mission’s Many ‘firsts’ Aim to Unlock Venus’s Hidden Secrets.” Phys.Org, 16 Dec. 2024, phys.org/news/2024-12-davinci-mission-firsts-aim-venus.html.

“Veritas.” NASA, www.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/veritas/.

David, Leonard. “The 1st Private Mission to Venus Comes Together Ahead of Possible 2026 Launch (Photos).” Space, 16 Mar. 2025, www.space.com/the-universe/venus/the-1st-private-mission-to-venus-comes-together-ahead-of-possible-2026-launch-photos.

“DAVINCI - NASA Science.” NASA, 10 Feb. 2025, science.nasa.gov/mission/davinci/.