Science behind cell size: to get big, make more DNA?

Your body is an assembly of individual cells. It is a statement that is perhaps too obvious to write. You may already know that living organisms are made up of many kinds of cells from the skin cells on your body to underlying muscle cells and blood cells that feed them with oxygen. But our vast collection of cells, 37 trillion by latest estimates, make up at least 200 different types of cells- a number that could still increase as we gain deeper understanding of the different denizens that call our bodies home.1

One immediate feature that separates these cells from one another is their physical size. In our bodies, the sperm cells constitute the smallest type, coming in at 30 cubic micrometres. For perspective, you can fit almost 1 million sperm cells into a single grain of sand. Compare that to the unfertilised egg cell, in which you could fit just 8 in one grain. 2,3 The disparity in size between two cells is about 100 000 fold. If you were to magnify the size of a single drop of water by the same amount, you would get a bowling ball.4,5

Despite the staggering range of size of cells in our bodies, choose just one type, and you will find that cells are more or less the same size.6,7 For example, doctors have known for some time that in healthy people, red-blood cells have a narrow size distribution.8 Somehow, cells in our body seem to know what size to reach and know how to maintain themselves at that size. Failure to do so often correlates with pathologies, such as anaemia for red-blood cells, or cancer more generally.6,8

The fact that it’s not the size of the cells per se that is worrisome, but rather the deviation from its usual size that can cause disease poses an interesting question: how do cells become large without the bad?

One possible hypothesis lies in the number of copies of DNA you have inside the cells. Most human cells have two copies of their genes inside the cell - one from the father and one from the mother. These two copies make up a single set. It appears that having more than one set, called polyploidisation, allows you to get much larger cells. This is the case in megakaryocytes, which may have up to 32 sets of genes, and puts it up to 15 times bigger than its cousin red blood cells.9

At an intuitive level, this seems to make sense. You may have heard of DNA as the blueprint for life, but genes are also a source of raw materials that make up the building itself. If you want to build a larger building, you are going to need more input.

Polyploidisation is also quite common and is not as dramatic as departure from everyday life. In fact, you have probably seen it before in your grocery stores. Most of the strawberries we eat nowadays are distinct from their smaller ancestors in that their large size stems directly from the strawberry plants’ ability to have many copies of its genes. In fact, many plant species adopt this method to increase their size.10

Figure 1. Reproduced from Irle and Schierenberg, 2002. Normal worm on bottom, larger polyploid worm on top. White bar on bottom left indicates 100um scale.

The hypothesis that polyploidisation allows for larger size leads to an experimental idea: what if we artificially increased the number of copies of genes in an organism? Would they become bigger? Luckily for us, German scientists in the early 2000s, Irle and Schierenberg, have done these kinds of experiments. To generate roundworms containing more copies of the gene, they fused two unfertilised eggs together (1 copy each = 2 copies) which were then fertilised by the sperm (1 copy) to yield one extra copy of the genes in total (3 copies compared to the usual 2 copies). The result was a bigger fertilised egg that then also developed into larger worms that were “up to 35% longer and also thicker than normal.”11

In these worms, the increase in individual cell size led to the increase in size of the organism itself. But curiously, it turns out that just because the size of the cell increases, doesn’t mean that the whole body size has to increase.

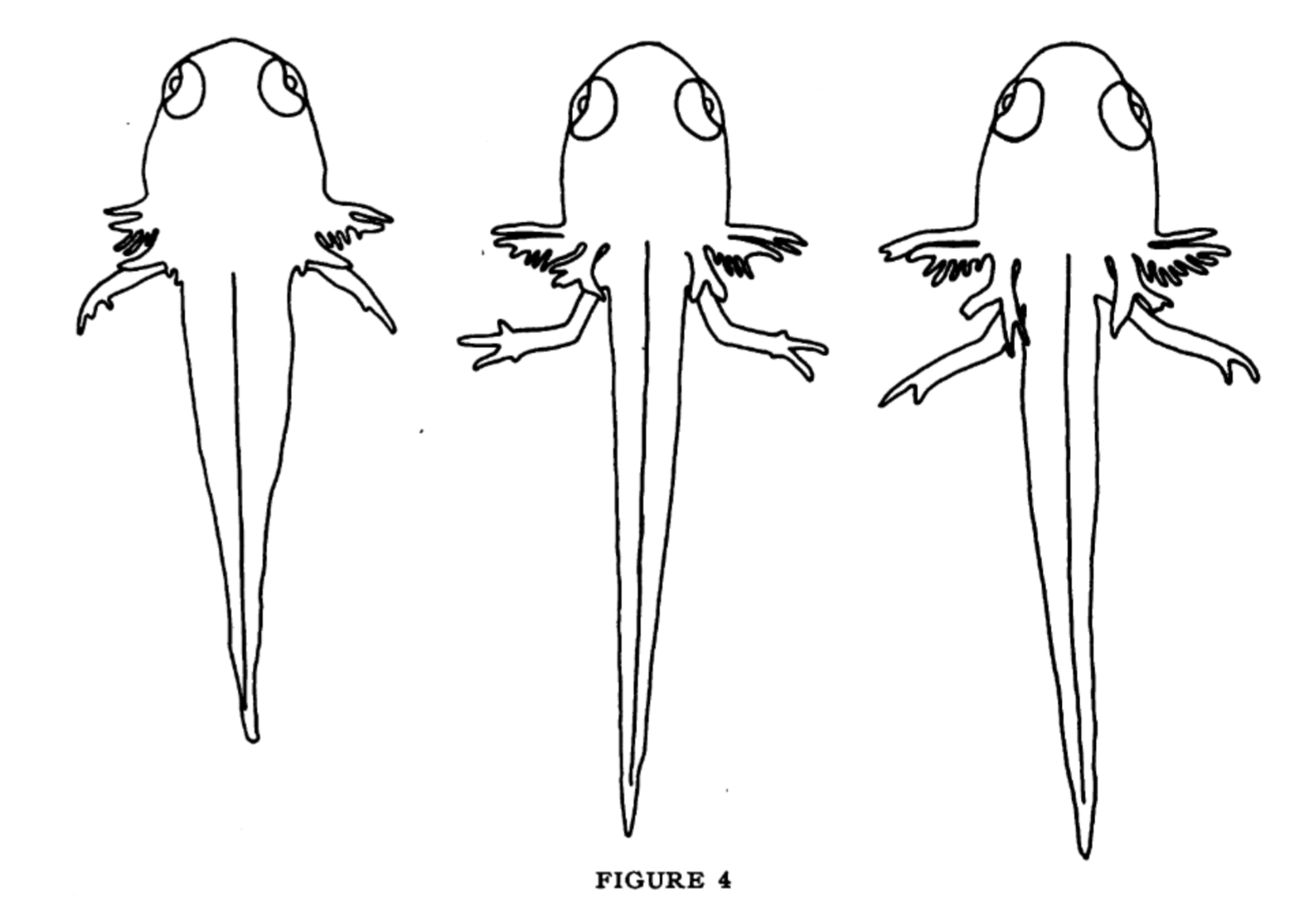

Enter Triturus Viridescens, or more simply, the newt. These amphibians normally develop with one set of genes in their embryos. However, sometimes they will also naturally develop from polyploid embryos. Fankhauser, a biologist at Princeton University, studied these polyploid embryos in the 1940s and saw that the increase in number of copies of genes in the newt embryo did not result in much change in size of the organism.12

Figure 2. Reproduced from Fankhauser and Griffiths, 1939. Tracing of enlarged newt larva, 4 weeks old. Ploidy increases from left to right: haploid, diploid, and triploid (1,2, and 3 sets of genes)

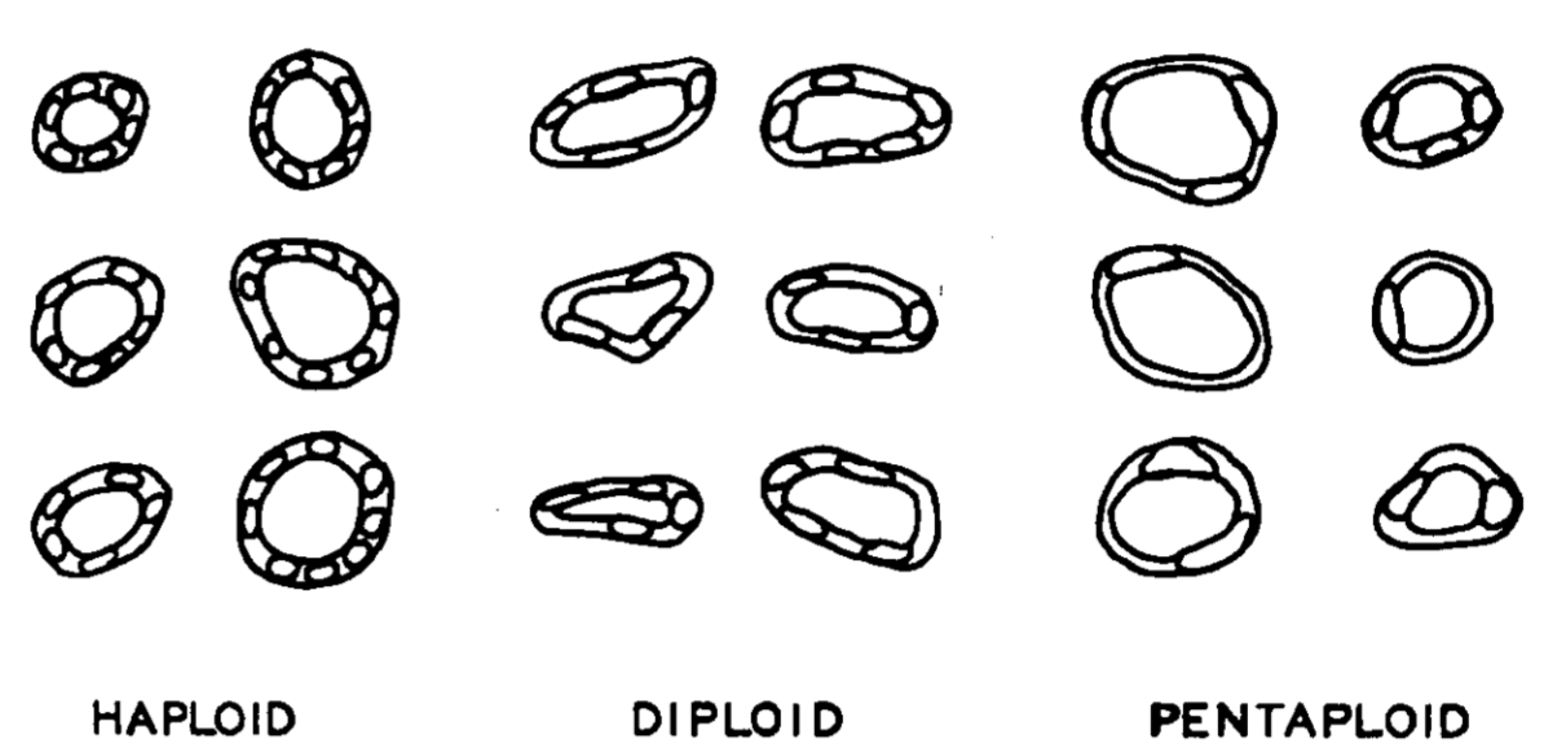

Peering closer, Fankhauser found that the indifference of the organism size to polyploidy was also true in the organs. In the pronephric duct, an organ that will eventually develop into urinary and reproductive tracts of the newt, the increase in cell size with ploidy was accompanied by the reduction in the cell numbers, keeping the overall size of the organ comparable to its normal size. The same was true also in the skin layer of the eye lens. What's more, the shape of these cells were also adjusted so that the organs maintained their overall normal shape.13

Figure 3. Reproduced from Fankhauser, 1945. Cross-sections of pronephric ducts of newts of different ploidy (haploid - one, diploid - two, pentaploid- five copies of genes). Notice the number and shape of cells are adjusted to maintain shape of organ

So now, we have two cases. One in which the increase in the number of sets of genes you have increases the body size, and the other that does not. In both instances, however, we see a near-proportional increase in the size of the individual cells. Our hypothesis that polyploidy leads to increase in size therefore seems to be true at the individual cell level, but not always true at the organism level.

This raises some interesting implications. Firstly, there may be some fundamental principle that links cell size with the number of sets of genes it has. Secondly, even when the size of the individual building blocks of the body is changed, animals can come up with ways that can correct for these changes at the body level.

How and why polyploidisation leads to bigger size remains mostly unresolved, but are an area of active research. For example in our lab, we study how the increase in cell size is coordinated with increase in production of its components.14–16 Understanding what allows the cells to become large will tell us how the cell utilises its genetic template with its growing needs, and these pathways may prove to be new avenues of counteracting uncontrollable cell growth and division, as seen in cancer.

REFERENCES

Bianconi, E. et al. An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Ann. Hum. Biol. 40, 463–471 (2013).

Wikipedia. Sand. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sand.

Milo, R. & Philips, R. How big is a human cell? http://book.bionumbers.org/how-big-is-a-human-cell/.

Staff Writer. What Is the Volume of One Drop of Water? https://www.reference.com/science/volume-one-drop-water-8164b654ac639858.

The Measure of Things. Is 5,000 milliliters as big as a Bowling Ball? https://www.themeasureofthings.com/singleresult.php?comp=volume&unit=ml&amt=5000&i=434.

Ginzberg, M. B., Kafri, R. & Kirschner, M. On being the right (cell) size. Science 348, 1245075–1245075 (2015).

Haldane, J. On Being the Right Size. Harper’s Magazine (1926).

Li, N., Zhou, H. & Tang, Q. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width: A Novel Predictive Indicator for Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases. Dis. Markers 2017, 1–23 (2017).

Davoli, T. & de Lange, T. The Causes and Consequences of Polyploidy in Normal Development and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 585–610 (2011).

Caseys, C. Up-Sizing: The Tale of The Polyploid Giants. https://medium.com/plant-cell-extracts/up-sizing-the-tale-of-the-polyploid-giants-508f9f7db (2018).

Irle, T. & Schierenberg, E. Developmental potential of fused Caenorhabditis elegans oocytes: generation of giant and twin embryos. Dev. Genes Evol. 212, 257–266 (2002).

Fankhauser, G. & Griffiths, R. B. Induction of Triploidy and Haploidy in the Newt, Triturus Viridescens, by Cold Treatment of Unsegmented Eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 25, 233–238 (1939).

Fankhauser, G. Maintenance of normal structure in heteroploid salamander larvae, through compensation of changes in cell size by adjustment of cell number and cell shape. J. Exp. Zool. 100, 445–455 (1945).

Lanz, M. C. et al. Increasing cell size remodels the proteome and promotes senescence. Mol. Cell 82, 3255-3269.e8 (2022).

Schmoller, K. M. & Skotheim, J. M. The Biosynthetic Basis of Cell Size Control. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 793–802 (2015).

Zatulovskiy, E. & Skotheim, J. M. On the Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Animal Cell Size Homeostasis. Trends Genet. 36, 360–372 (2020).