BABY FACE(BOOK)

COVID VACCINES MINISERIES PART 3: ANTI-VAXX BELIEFS AREN’T NEW… BUT THEIR SOCIAL MEDIA PRESENCE IS.

Anyone who’s ever been on Facebook probably knows a little something about the anti-vaxx movement. Promoting everything from full-on conspiracy theories to more subtle pushes for people to reject vaccines, anti-vaxx communities are a real threat to public health 1 . Further, politicization and distrust surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic has only compounded the issue. 49.0% of the US and 14.4% of the world population have been fully vaccinated for COVID-19 2 , but humanity is still very far away from reaching herd immunity - the 95%-vaccinated threshold necessary to protect our most vulnerable populations 3 . There are many reasons we aren’t quite there yet. For the developing world, access is the biggest barrier 4 , and richer countries are only donating a very small percentage of their vaccine doses 5 . Among developed countries, the reasons are complex and multifaceted. Although access is still a major barrier for some groups 6 , others are better described as vaccine hesitant 7,8 . Not quite staunchly anti-vaxxers, but certainly not pro-vaccine, these people have doubts about the COVID-19 vaccines or vaccines in general. In the previous two articles in our COVID Vaccines miniseries (Part 1 here and Part 2 here), you’ve learned about the science behind vaccination and explored the numbers behind COVID-19 vaccine safety and effectiveness. Here, we’ll explore the history and present-day operation of the anti-vaccine movement.

THE HISTORY OF VACCINES (AND ANTI-VAXXERS)

Vaccination may be modern technology, but the science behind it is nothing new. For over 1000 years, people have noticed that exposure to a disease as a child prevents severe disease later in life. Smallpox was one of the first diseases people tried to curtail - it killed over a third of infected adults and 80% of infants, and those that survived had disfiguring scars that even drove some to suicide 9 . Over 1000 years ago in China and India, people inoculated (exposed to a disease) their children for smallpox by grinding up scabs from people with smallpox and blowing them into the children’s nostrils 10 . The practice then evolved into variolation, in which a person would rub scabs or pus from a person with smallpox into scratches in their own skin. This was used in Africa and Asia since at least the 16th century, and was eventually introduced to North America in the early 18th century by an enslaved African man named Onesimus. His slaveowner Cotton Mather attempted to popularize the idea in his Boston community, but was met with ridicule 6 .

Figure 1: Chinese print showing vaccination, 1913 [10]

Meanwhile in England, the observation that milkmaids seemed to be immune to smallpox motivated farmer Benjamin Jesty and doctor Edward Jenner to independently investigate. Turns out, the milkmaids had all previously contracted cowpox, a much milder disease that left them immune to the related smallpox virus. Testing the theory, Jesty scratched cowpox scabs into scratches on his wife and sons, while Jenner tried the same on a young boy. None of them contracted smallpox. From these experiments, modern vaccination (using a less potent form of a disease to produce an immune response) was born. It was much safer than variolation - and it worked. Jenner published his results, and the buzz spread across Europe, eventually reaching the rest of the world and saving millions of lives 9 .

Back in England, the Vaccination Acts of 1853 and 1867 required English citizens to vaccinate infants and children and imposed penalties if they didn’t. But not everyone was sold on the idea. Some people at the time believed that smallpox vaccination was “unchristian” because cowpox was derived from an animal. Others were wary of Jenner’s theories on disease spread (germs were a fringe theory at the time). And some thought vaccination was an infringement on personal liberties. Protests of the Vaccination Acts were eventually successful, and an 1898 law removed the penalties for non-compliance as well as allowed people to get exemptions 11 .

Figure 2: “The Cow Pock” - An 1802 political cartoon by James Gillray expressing fear that the cowpox-based smallpox vaccine would lead to outrageous cow-like side effects. [Wikimedia Commons]

Meanwhile, in the early 1900’s United States, smallpox outbreaks continued to threaten public safety and prompted Cambridge, Massachusetts to mandate vaccination for all city residents. When one resident objected, his case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled that states could enforce mandatory vaccination in a public health crisis. In the 1970s, anti-vaccine sentiment rose again in England in response to allegations that the Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis (DTP) vaccine caused neurological damage in children. Vaccination rates decreased dramatically and caused three major epidemics of whooping cough in the UK 11 .

More recently, in 1998, British doctor Andrew Wakefield published an extremely scientifically flawed study claiming a link between the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine and inflammatory bowel disease and autism. Although the paper was retracted (taken back due to fraud or inaccuracy) and Wakefield was struck from the medical register in Great Britain, the harm he caused is still evident today 12 . Directly, outspoken celebrities continue to perpetuate the erroneous link between vaccines and autism, and more indirectly, the controversy seeded doubt and mistrust that impacts public attitudes toward science. We see echoes of these historical anti-vaxx movements in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Certain groups in the United States view mask-wearing, quarantining, and vaccination as infringements on civil liberties, just as English citizens did in the late 1800s. Other people doubt or misunderstand the science of vaccination, similarly to how early opponents of Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine did not understand how disease actually spread. Still other vaccine-hesitant groups cite safety concerns, mirroring fears of side effects and neurological damage sensationalized by the media in the late 20th century. The anti-vaccine arguments we see today aren’t new. But they’re still extremely problematic - dips in vaccination rates are quickly followed by outbreaks of completely preventable disease, causing unnecessary deaths and leaving vulnerable populations, like infants, the elderly, and the immunocompromised, completely unprotected 6 .

THE MODERN ANTI-VAXX MOVEMENT

The recent rise in anti-vaccine sentiment follows a key shift in how information spreads. For the 18th, 19th, and most of the 20th centuries, people got their information from newspapers, and more recently, radio and television media. Generally, the editorial process worked - journalists collected information from primary sources, and editors internally checked stories for quality before releasing them to the general public. Even the early internet (Web 1.0) didn’t disrupt this process too much. But the shift to Web 2.0 changed everything. Web 2.0 refers to the modern way that people use the internet - we focus less on central content creators, like news outlets, and place more of an emphasis on user-generated content. Social media, like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, allow individuals to interact and influence one another directly, rather than having information filter down through central news authorities. From a healthcare perspective, this has given people more agency in medical decisions - instead of doctors telling patients what to do or what treatments to take, healthcare is viewed as more of a conversation between doctor and patient. But empowering individuals in this way can also be very harmful. When anyone can be an expert (from the self-proclaimed “University of Google”), the legitimacy of doctors and scientists is undermined and trust decreases. In addition, the focus on user-generated content allows vocal minority groups to seem larger than they actually are. Fringe communities, like flat-Earthers and Holocaust deniers, can now easily find like-minded people and create a disproportionately large online presence, leading others to believe that these radical theories are actually commonplace 13 . Anti-vaxxers have similarly found their home on social media, where they spread misinformation like wildfire. But these aren’t just random concerned mothers here and there. In 2020, researchers at the Center for Countering Digital Hate uncovered well-established groups of professional propagandists (with as many as 60 staff each) seeding anti-vaxx information online. These groups work to develop misinformation campaigns applicable to different audiences, secure government funding, and even hold conferences 1 . This is all going on behind-the-scenes; meanwhile, all you see is a subtle anti-vaccine post every so often in your news feed.

Figure 3: An anti-vaccination protest taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The problem is that these campaigns work. Anti-vaxxer social media accounts have attracted more than 7.8 million new followers since 2019 14 , upping the total count to 59 million 1 . On YouTube, 17 million people subscribe to anti-vaxx accounts 14 . Even more surprising, anti-vaxx YouTube videos comprise 32% of all immunization-related videos, and these videos have more views and higher ratings than pro-immunization videos 13 . This can steer casual, curious visitors toward even more anti-vaxx content. On Facebook, a whopping 31 million people follow anti-vaxx groups 14 . In one study 15 of over 100 million individual Facebook users, researchers found that anti-vaccine communities, though smaller in size than pro-vaccine groups, are more highly connected within the social network. Not only do they have extensive links between each other, but they also have more links to groups that are still undecided about vaccines. This means that anti-vaxxers have huge influence over undecided people. Additionally, the variety of groups that the anti-vaxx movement provides allows them to attract undecided people easily, as each new person feels that they really resonate with a particular subgroup 15 . This is true outside of Facebook as well, where anti-vaxx websites take extremely diverse approaches. Some are very direct, like SafeMinds, Generation Rescue, and Age of Autism, which all continue to overtly claim vaccines are linked to autism. Others pretend to be objective and scientific to appeal to people’s logical minds, like the National Vaccine Information Center, Vaccination Risk Awareness Network, and Australian Vaccination Network. Still others employ a focus on family and health to subtly deliver anti-vaxx information, like NaturalNews.com, Mercola.com, and Mothering.com 13 The wide variety of slightly different outlooks and niche opinions on vaccination makes more and more people feel welcome in the movement. The Facebook analysis15 also showed that medium-sized anti-vaccine groups are growing the fastest, particularly after vaccine-preventable outbreaks like the measles outbreak of 2019. Because typically only the largest anti-vaxx groups are on pro-vaccine groups’ radar, these mid-size clusters often go unnoticed, attracting more and more people to their cause every day 15 .

Figure 4: Anti-vaxx Facebook groups (red) have more connections between each other and to undecided groups (green) than do pro-vaccination groups (blue). They are also growing the fastest and have global connectivity. [15]

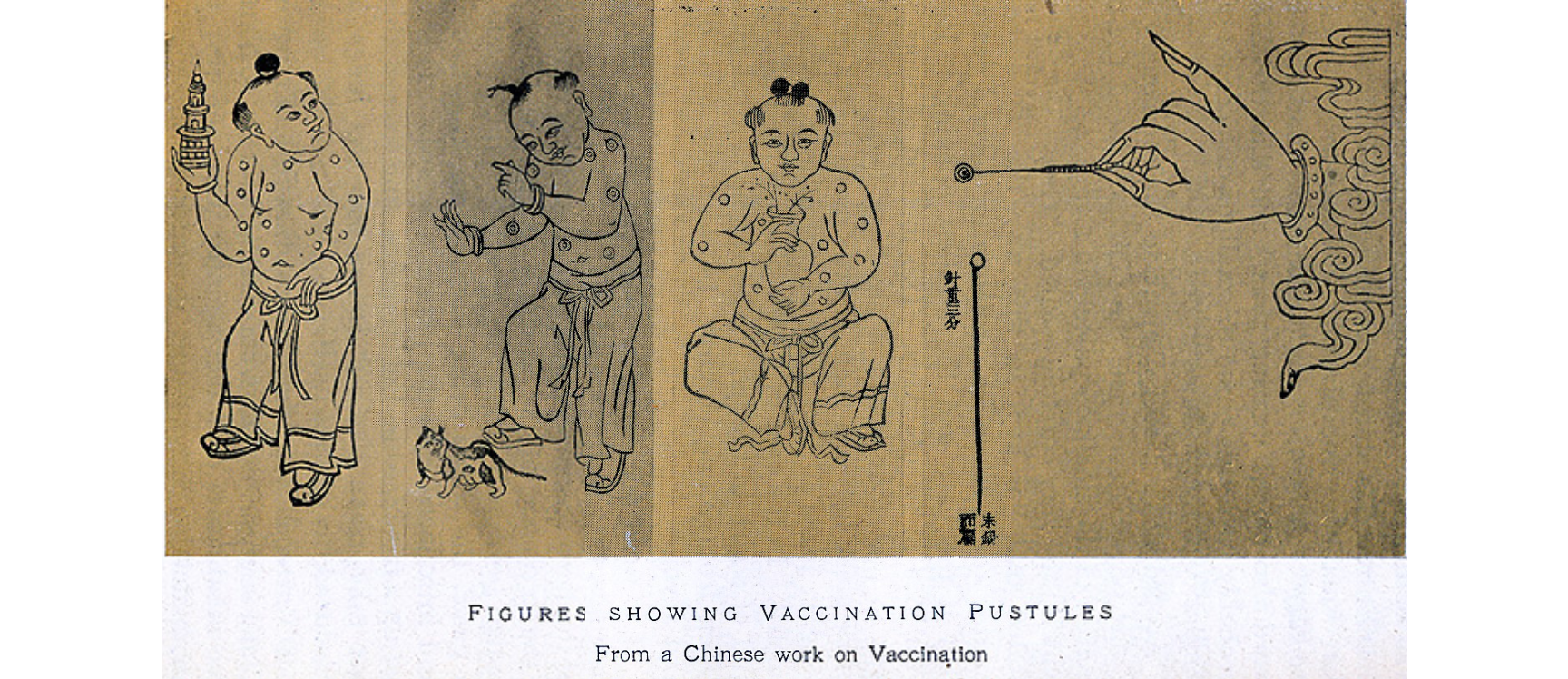

Why are these anti-vaxx accounts doing so well? It comes down to advertising. Because these pages receive a lot of visitors, social media companies like Facebook and Instagram stand to make $989 million by advertising on these pages. In addition, the products being advertised matter. Anti-vaxx page visitors are more likely to click on ads and eventually purchase anti-vaxx products, like homeopathy treatments and ‘’natural” medicine, further cementing their anti-vaccine beliefs 14 . When advertisers and social media companies are both making money off anti-vaxxers, they have virtually no incentive to combat the issue 1 . Luckily, backlash from users has caused many social media companies to make pledges to actively counteract anti-vaccine sentiment on their platforms. YouTube removed ads from anti-vaxx content so that the creators couldn’t make any money and Facebook pledged to stop recommending anti-vaxx content to its users. Facebook and Twitter both employ fact-checkers to place labels on dubious content, either warning people about misinformation or providing links to trusted websites where users can learn more about vaccines. Though these steps should reduce the influence of anti-vaxxers in theory, fewer than 1 in 20 such posts are actually dealt with 14 . Banning certain individuals from social media platforms is a potential way to stop the problem, and is completely legal since moderation decisions are protected by law 1 . Twitter has certainly gone in that direction by permanently suspending accounts that promote vaccine misinformation, such as former president Donald Trump’s. Yet Twitter has not suspended Jenny McCarthy, former model and actress who previously used the platform extensively to promote Andrew Wakefield’s fraudulent “vaccines cause autism” claim. Although removing individuals would fragment the anti-vaxx network considerably, there are legitimate concerns about censorship and the right to free speech. It may start with simply removing anti-vaxx posts and users that repeatedly post misinformation on the platform, but it could quickly spread to removing users who promote misinformation in real life. Additionally, removing anti-vaxxers from social media may even add fuel to the fire when these individuals claim oppression and censorship 14 . It’s tricky where to draw the line with blocking misinformation, and experts have many different perspectives on how to deal with this crisis. We'll talk about the specific ways you can combat misinformation in your own life in Part 5 of this miniseries.

Figure 5: Anti-vaccine pages were the top suggestions after typing “vacci” on Facebook, 2018.

CONCLUSION

Anti-vaccine arguments have been around nearly as long as vaccines themselves. Whether for smallpox in the 1800s or COVID-19 today, anti-vaxxers have claimed threats to individual liberties, unfounded concerns about health and safety, and misinformed doubts about need and effectiveness. While the meat of their arguments has remained largely the same over the centuries, the modern internet and social media have provided explosive platforms for misinformation and anti-vaxx sentiment to spread. Next week, we’ll take a closer look at some of the specific arguments anti-vaxxers use to justify their beliefs, so you can point out the flaws in their reasoning.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Imran. “Dismantling the Anti-Vaxx Industry.” Nature Medicine, vol. 27, no. 3, 2021, p. 366. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01260-6.

Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Diana Beltekian, Edouard Mathieu, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Charlie Giattino, Cameron Appel, Lucas Rodés-Guirao and Max Roser (2020) - "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

“Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Herd Immunity, Lockdowns and COVID-19.” World Health Organization, 31 Dec. 2020, www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19?gclid=Cj0KCQjw0K-HBhDDARIsAFJ6UGhO_Vdn9zclyXtZ6pZ9nvyJLEUCr14tmUS-7SX4dbyBRz2xoG55pvwaAuh8EALw_wcB#.

Cuddy, Alice. “Coronavirus Vaccines: Will Any Countries Get Left Out?” BBC News, 22 Nov. 2020, www.bbc.com/news/world-54961045.

BBC News. “Covax: How Many Covid Vaccines Have the US and the Other G7 Countries Pledged?” BBC News, 11 June 2021, www.bbc.com/news/world-55795297.

Leask, Julie. “Vaccines — Lessons from Three Centuries of Protest.” Nature, vol. 585, no. 7826, 2020, pp. 499–501. Crossref, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02671-0.

Simas, Clarissa, and Heidi J. Larson. “Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy in Low-Income and Middle-Income Regions.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00279-w.

Sobo, Elisa J., et al. “Black and Latino Communities Often Have Low Vaccination Rates – but Blaming Vaccine Hesitancy Misses the Mark.” PBS NewsHour, PBS, 8 July 2021, www.pbs.org/newshour/health/black-and-latino-communities-often-have-low-vaccination-rates-but-blaming-vaccine-hesitancy-misses-the-mark.

Hollingham, Richard. “The Chilling Experiment Which Created the First Vaccine.” BBC Future, BBC, 29 Sept. 2020, www.bbc.com/future/article/20200928-how-the-first-vaccine-was-born.

“Timeline.” The History of Vaccines, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 2021, www.historyofvaccines.org/timeline/all#EVT_1.

“History of Anti-Vaccination Movements.” The History of Vaccines, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 10 Jan. 2018, www.historyofvaccines.org/index.php/content/articles/history-anti-vaccination-movements.

Omer, Saad B. “The Discredited Doctor Hailed by the Anti-Vaccine Movement.” Nature, vol. 586, no. 7831, 2020, pp. 668–69. Crossref, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02989-9.

Kata, Anna. “Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm – An Overview of Tactics and Tropes Used Online by the Anti-Vaccination Movement.” Vaccine, vol. 30, no. 25, 2012, pp. 3778–89. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112.

Burki, Talha. “The Online Anti-Vaccine Movement in the Age of COVID-19.” The Lancet Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 10, 2020, pp. e504–05. Crossref, doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(20)30227-2.

Johnson, Neil F., et al. “The Online Competition between Pro- and Anti-Vaccination Views.” Nature, vol. 582, no. 7811, 2020, pp. 230–33. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1.

![Figure 2: “The Cow Pock” - An 1802 political cartoon by James Gillray expressing fear that the cowpox-based smallpox vaccine would lead to outrageous cow-like side effects. [Wikimedia Commons]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607773ecd359161f2364e7c9/1627607913718-C2N2MJU9G83YDQIH49K5/The_cow_pock.jpeg)

![Figure 4: Anti-vaxx Facebook groups (red) have more connections between each other and to undecided groups (green) than do pro-vaccination groups (blue). They are also growing the fastest and have global connectivity. [15]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607773ecd359161f2364e7c9/1627664694250-QMPWVOKRB1ET8OSER4WQ/clusters.png)