10 DEEP-SEA FISH THAT LOOK JUST LIKE GOLLUM - NUMBER 8 WILL SHOCK YOU

“There are strange things living in the pools and lakes in the hearts of mountains: fish whose fathers swam in, goodness only knows how many years ago, and never swam out again, while their eyes grew bigger and bigger and bigger from trying to see in the blackness… Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum, a small slimy creature… dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face” (The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien; Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gollum from J.R.R. Tolkien's book The Hobbit. (1)

While Tolkien probably wasn’t discussing deep-sea fish in his famous novel, he touched on one of the key adaptations among animals subjected to extreme darkness - their eyes. Just like Gollum with his large, pale eyes, many fish species have maximized their eye size (among other characteristics) in order to see as much as possible in an extremely dark environment (Figures 1, 2). These extreme adaptations are not only a beautiful example of the power of evolution, but they also give us key insights toward understanding vision and perception as a whole.

Figure 2: The Pacific blackdragon, a deep-sea fish. (2)

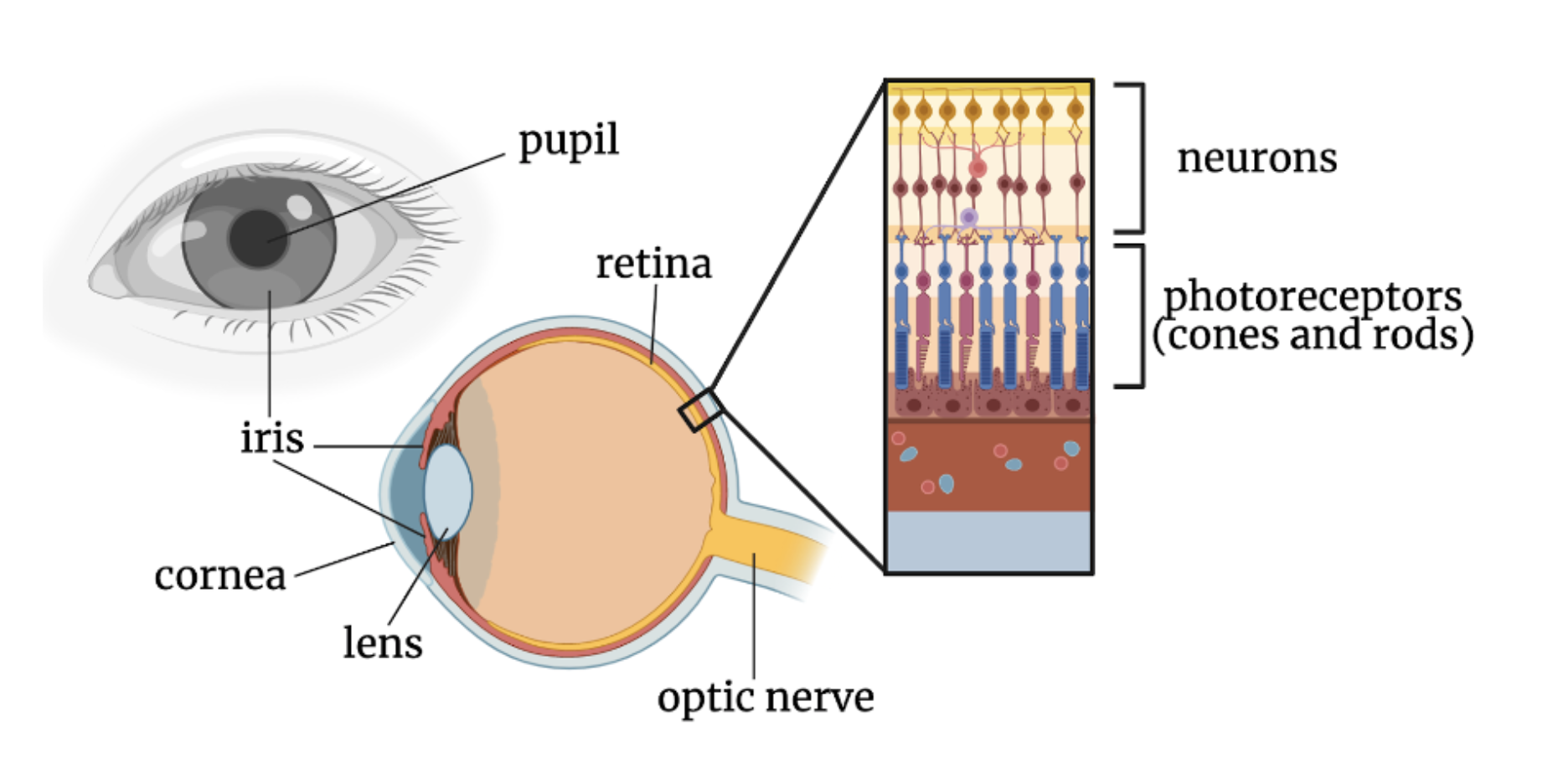

Eye Anatomy

Before diving into the specializations of deep-sea fish eyes, it’s important to understand the general anatomy and function of eyes. Eyes are special organs that take in light from the environment, convert it to neuronal signals, and translate it into what we see. To do this, eyes need a few basic structures (some structures not included, for the sake of brevity):

Cornea: outermost part of the eye; a “window” that takes in light

Iris: controls the aperture (or opening) of the pupil by changing size based on the amount of light

Pupil: the opening, where light enters inside the eye

Lens: located behind the pupil, iris, and cornea; focuses light for the retina

Retina: at the very back of the eye; converts the light into neural impulses

Photoreceptors (Rods and Cones): specialized cells in the retina that convert the light

Rods: respond to low light levels; can’t be used for color vision and have low spatial resolution

Cones: respond to high light levels; used for color vision and have high spatial resolution; different types of cones are specialized for different colors

Optic Nerve: the nerve fibers that carry the converted signals back to the brain, where they become what we see (3,4)

Figure 3: Diagram of the anatomy of the eye, which is made up of the iris, pupil, cornea, lens, retina, optic nerve, neurons, and photoreceptors. Created with BioRender.com.

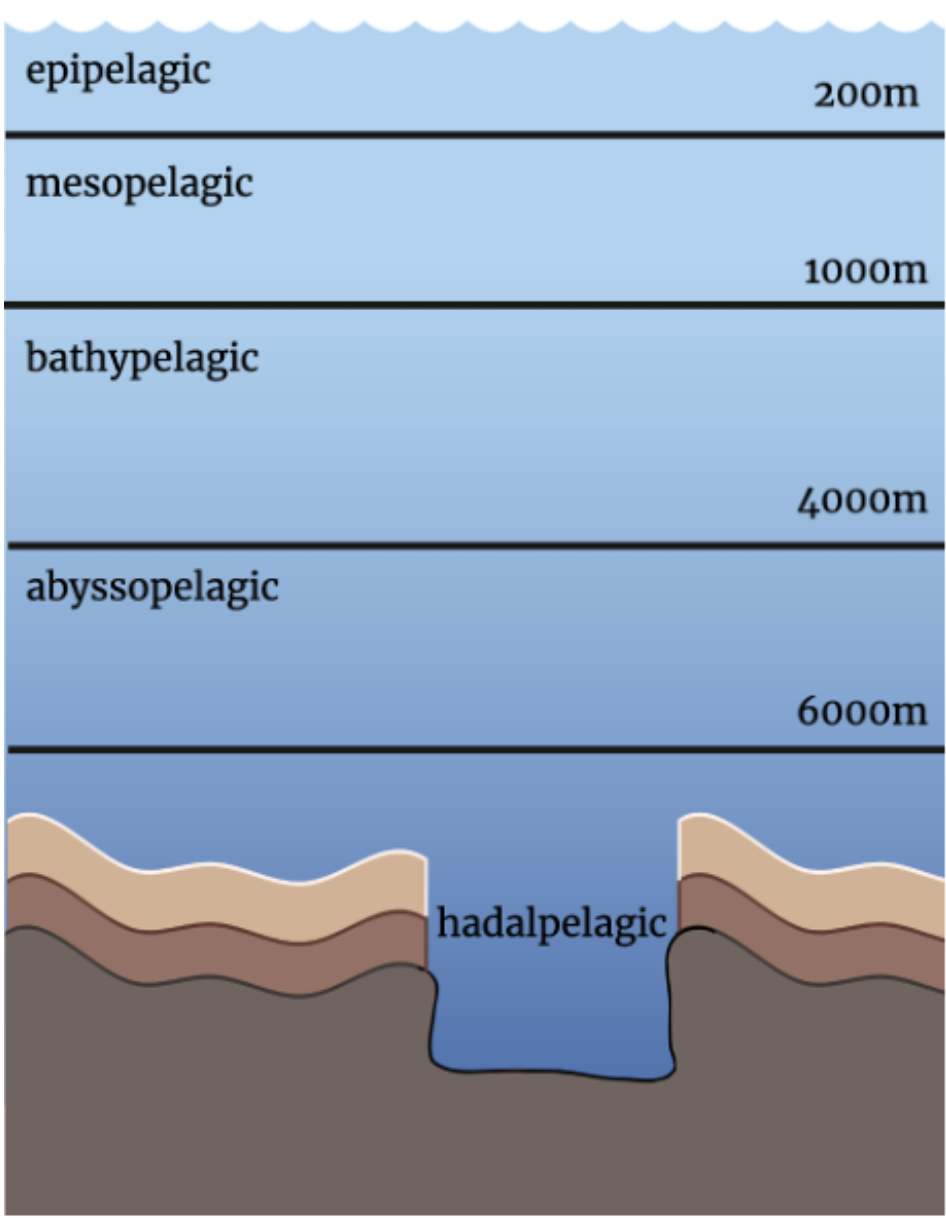

Ocean Zones

Ocean depths are categorized into 5 zones (Figure 4). Because water absorbs light, it gets darker the deeper you go in the ocean. There are two zones in the ocean where light is especially limited and fish have unique visual adaptations: the mesopelagic or “twilight” zone and the bathypelagic zone. In the mesopelagic zone (200-1000 meters below the surface), a tiny bit of sunlight from the surface can penetrate, but not much. The small amount of light that can penetrate is limited to blue and green wavelengths. In the bathypelagic zone (1000-4000 meters), there is no remaining sunlight. The only light organisms can see here is bioluminescence. Bioluminescence is light which is produced by organisms using biological functions. For example, fireflies and anglerfish (like in Finding Nemo) are bioluminescent. Sunlight and bioluminescence are two different types of light, and as such, fish in the bathypelagic vs. mesopelagic zones sometimes have different adaptations.

Figure 4: Diagram of the different ocean zones and their depths. Created with BioRender.com.

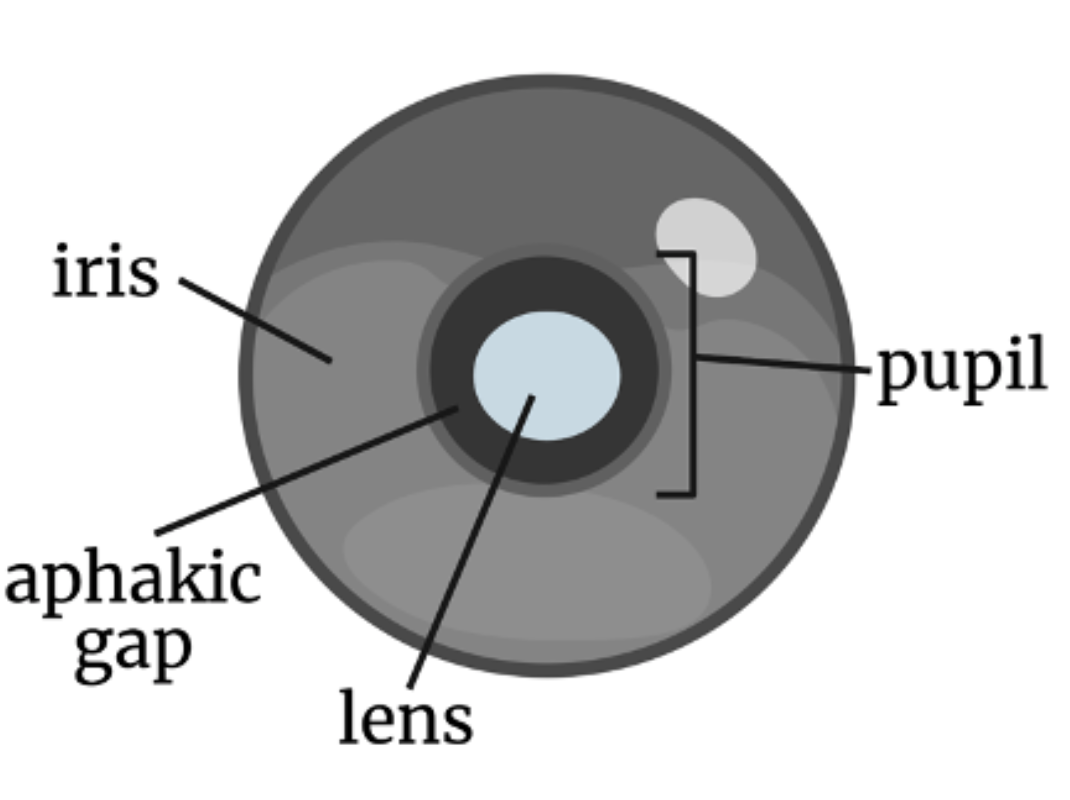

Eye and Pupil Size

One adaptation that can be found in both the bathypelagic and mesopelagic zones are increased eye and/or pupil size. Have you ever been outside on a sunny day, and then walked into a dark building? You most likely couldn’t see much of anything at first, until your eyes adjusted to the dimmer light. When your eyes adjust, your pupils become larger as the iris retracts back. A larger pupil lets more light enter at once, allowing you to see even in darker places.

Fish in the deep ocean have evolved large pupils over time, since they’ve lived in a dark location for millions of years. Some fish species do this by simply having larger eyes, which results in proportionally larger pupils. Other fish species have disproportionately large pupils relative to their eye size, giving them something called an aphakic gap (Figure 5). In these fish, the aphakic gap is the region of the pupil that extends past the lens of the eye. Although the larger pupil increases the amount of light that can enter the eye, the lens is limited in how much of the light it can focus. This increases the sensitivity of the eye at the cost of spatial resolution - like an unfocused camera, the image is blurry. (5,6)

Figure 5: Diagram illustrating the aphakic gap, which is the region of the pupil that expands past the lens. Created with BioRender.com.

Tapetum Lucidum

In extreme darkness, every ray of light is vital for a fish’s survival - a fish that can see is a fish that can escape predators. To collect as much light as possible, deep-sea fish have a reflective layer of tissue at the back of the eye, called a tapetum lucidum. This tissue reflects unabsorbed light back into the photoreceptors, thus increasing the amount of light collected. Many animals with night vision, such as cats and raccoons, have tapetum lucidum. You may have noticed this if you’ve ever taken a flash photograph of your cat in the dark and noticed the eyes shining! Unfortunately, like many other adaptations in deep-sea fish, the tapetum lucidum blurs the image that the fish see. When the light is reflected, the rays scatter and lose focus, making the image blurrier. But since the deep ocean is so dark, the increased amount of light gathered is worth the loss in resolution. (6)

Increased Rods

The eye has two types of photoreceptors: rods, which respond to low light levels, and cones, which respond to high light levels. Given the low level of light in the mesopelagic and bathypelagic zones of the ocean, most fish that live there have rod-dominated retinas. When there are never high levels of light around, cones become unnecessary and are eventually lost over the course of evolution. As always, this adaptation comes at the expense of spatial resolution.

Researchers used to think that the lack of cones in deep-sea fish meant they also lacked color vision. But some recent research on a specific rod protein in three species of fish (tube-eyes, lanternfishes, and spiny-fins) has made some scientists question that assumption. Rod opsins are a special type of protein in rods that are sensitive to light and help convert light into neural impulses. Researchers at University of Basel, University of Western Australia, University of Idaho, University of Queensland, and a few other research institutes worked together and found that these fish had many copies of the rod opsin RH1, while most other fish species only have one. Currently, the researchers have 5 hypotheses for why RH1 is duplicated:

They could give the fish conventional color vision, where they see a similar color spectrum to us or to other fish species.

They could give the fish unconventional color vision, where they see a unique color spectrum from other species.

They could increase the retinal sensitivity, such that the fish can see well with extremely low levels of light.

They could increase light spectrum sensitivity, such that the fish can see light in a broad range of wavelengths.

They could increase contrast, making darks and lights more distinct.

While research on these rod opsins is still ongoing, the prospect that these fish could see color is intriguing. (7)

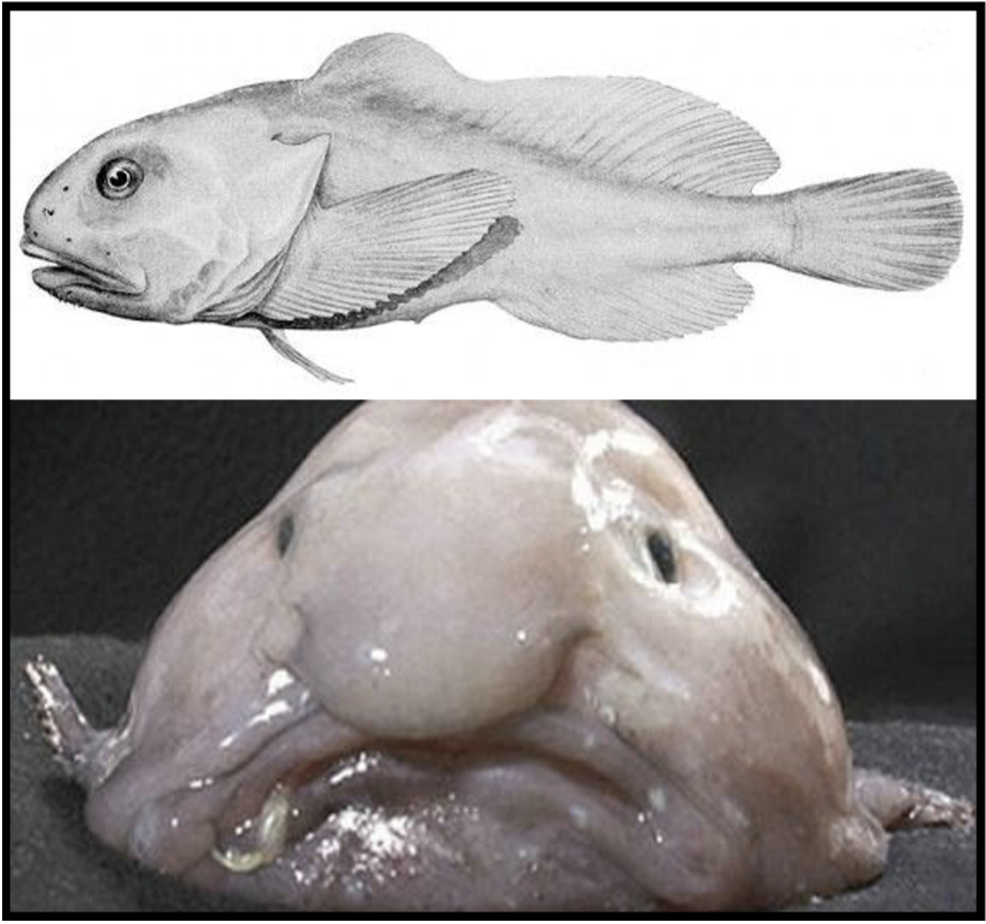

Figure 6: Top: An illustration of the Blobfish as it would appear in the deep sea. Bottom: Image of the infamously ugly Blobfish after being brought to the surface. The transfer from the high-pressure deep sea to the low-pressure surface destroys its delicate tissues. (8)

Conclusion

Deep-sea fish are amazing examples of the power of evolution and the extremes of vision and perception. With scarce light, these fish have evolved special eyes that are very different from our own, allowing them to see enough to survive in the deep ocean.

Yet there is still a lot of research left to do on the amazing visual adaptations of these deep-sea fish. Part of the challenge is actually obtaining fish to study. The deep ocean is extremely cold, deep, dark, and highly pressurized. As such, getting research vessels (let alone human scientists) down to those depths is a huge challenge. Additionally, specimens must be returned to land very carefully. Just as humans can get “the bends” from changing pressure too quickly, these delicate fish can be destroyed by going from high to low pressure (Figure 6). (6) With technological advancements, it will become easier to research these phenomenal animals and gain a deeper understanding of both vision and evolution.

Sources

Peplow, Gemma. "Gollum star Andy Serkis to give 12-hour live reading of The Hobbit – with ‘all the voices.’” Sky News, May 7 2020, https://news.sky.com/story/gollum-star-andy-serkis-to-give-12-hour-live-reading-of-the-hobbit-with-all-the-voices-11984409.

Photograph: Karen Osborn/Smithsonian. Remmel, Ariana. “Ultrablack skin camouflages deep sea fish.” Chemical & Engineering News, July 16 2020, https://cen.acs.org/materials/biomaterials/Ultrablack-skin-camouflages-deep-sea/98/i28.

Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan Health. https://www.umkelloggeye.org/conditions-treatments/anatomy-eye

Rochester Institute of Technology. https://www.cis.rit.edu/people/faculty/montag/vandplite/pages/chap_9/ch9p1.html.

Busserolles et al. “The exceptional diversity of visual adaptations in deep-sea teleost fish.” Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology, October 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.05.027.

Priede, Imants. “Adaptations to the Deep Sea.” Cambridge University Press, August 2017, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/deepsea-fishes/adaptations-to-the-deep-sea/594899C502F534259535DE1745CFD96B.

Musilova et al. “Vision using multiple distinct rod opsins in deep-sea fishes.” Science, May 10 2019, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/364/6440/588.

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons. Illustration: Alan Riverstone McCulloch/Wikimedia Commons. Schultz, Colin. “In Defense of the Blobfish: Why the ‘World’s Ugliest Animal’ Isn’t as Ugly as You Think It Is.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 13 2013,https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/in-defense-of-the-blobfish-why-the-worlds-ugliest-animal-isnt-as-ugly-as-you-think-it-is-6676336/.