WHAT IS (AND WHAT ISN’T) EVOLUTION

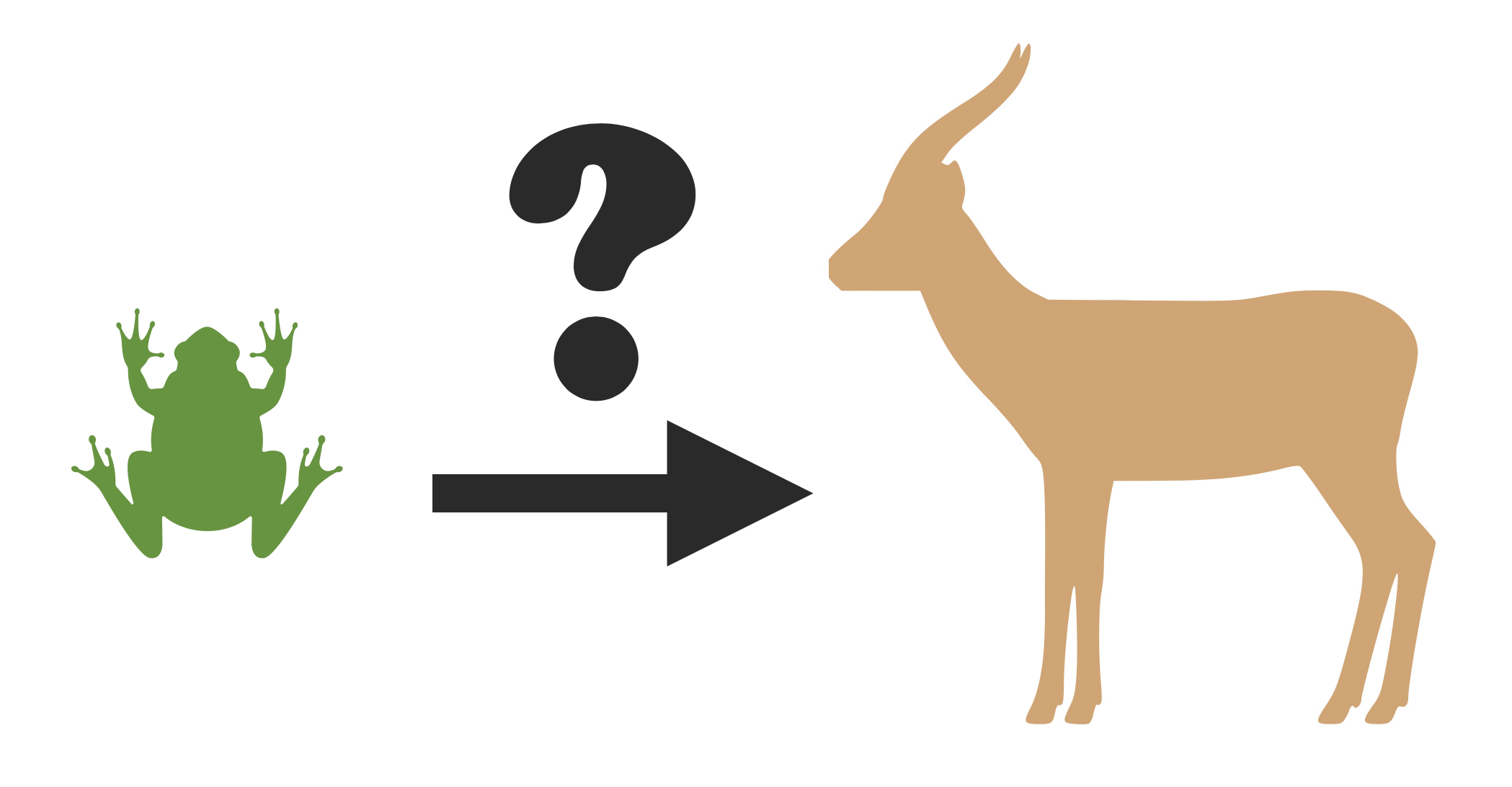

IF YOU PUT A FROG IN A DESERT, COULD IT BECOME A GAZELLE?

Evolution is fundamental. Evolutionary thinking enhances our understanding of molecular and developmental biology, genetics, ecology, and more. Biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky said it best: “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

But despite its importance, there’s still a lot of confusion surrounding evolution. Once on a public bus, a fellow rider asked me, “Isn’t evolution, like, if you put a frog in a desert and it becomes a gazelle?”

Sure, that’s a little silly. But his question actually points to some key, common misunderstandings about evolution. So before we dive into what evolution is NOT, let’s talk about its formal definition.

WHAT IS EVOLUTION?

Evolution is a change in the characteristics of a population over a long time. For example, the ape ancestors of humans were hairy, but this was lost over time as they evolved into relatively-hairless modern humans.

Maybe this gave early humans an advantage, or maybe it just tagged along when a bunch of other changes were taking place. We’ll talk more about this distinction in a bit. But in any case, we say that humans evolved hairlessness.

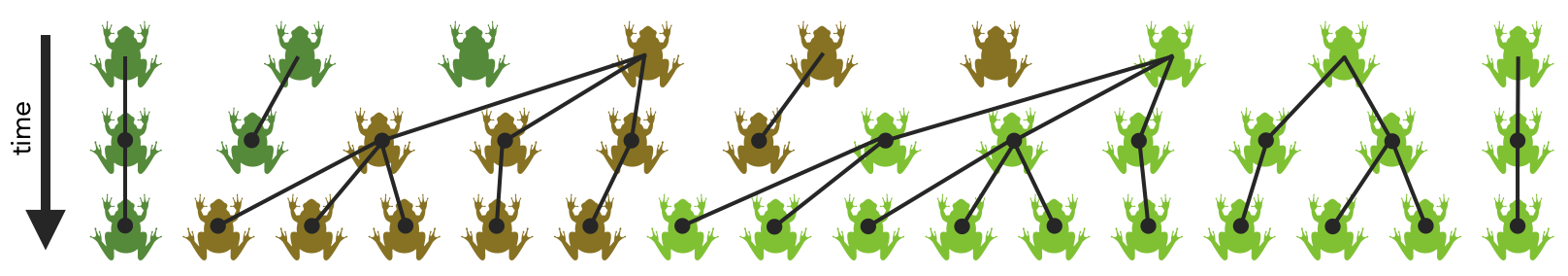

People commonly think evolution is the same as natural selection, but actually, natural selection is just one way evolution can take place (you can learn about the other ways here). Natural selection happens when the environment selects which individuals survive and reproduce; individuals that survive better in a certain environment are more likely to reproduce and pass on their genes to the next generation.

There are equal numbers of dark green, brown, and light green frogs in the starting population. But the light green frogs are better able to survive and have babies, so in three generations, light green frogs make up the majority of the population. Image: AL Fortier

Thus, over many generations, individuals that are better-adapted to the environment become more prevalent in the population. So the population changes over time—it evolves!

Now that we have the basics, let’s tackle some common misconceptions about evolution!

EVOLUTION MYTHS

For explanations of even more evolution misconceptions, check out this resource!

EVOLUTION HAS TO OCCUR NATURALLY.

Evolution doesn’t have to rely on just natural selection. Humans have artificially selected tons of species. We’ve created dog breeds, show pigeons, larger fruits and veggies, and higher-yield crops by selectively breeding together specific individuals with traits that we want.

EVOLUTION IS A SLOW PROCESS.

Evolution has to take place over successive generations, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it has to take millions of years. For example, lactase persistence—which allows humans to digest milk as adults—has been evolving super rapidly. It appeared only about 7,500 years ago (or around 300 generations) and has already reached nearly 100% frequency in northern Europe.1 That’s pretty short in the grand scheme of evolutionary time!

Evolution can happen even more rapidly under certain conditions. For example, small population sizes, really beneficial or really detrimental traits, and extreme environmental shifts (like an asteroid strike or climate change) can all kick-start rapid evolution.

EVOLUTION HAPPENS WITH AN END GOAL IN MIND.

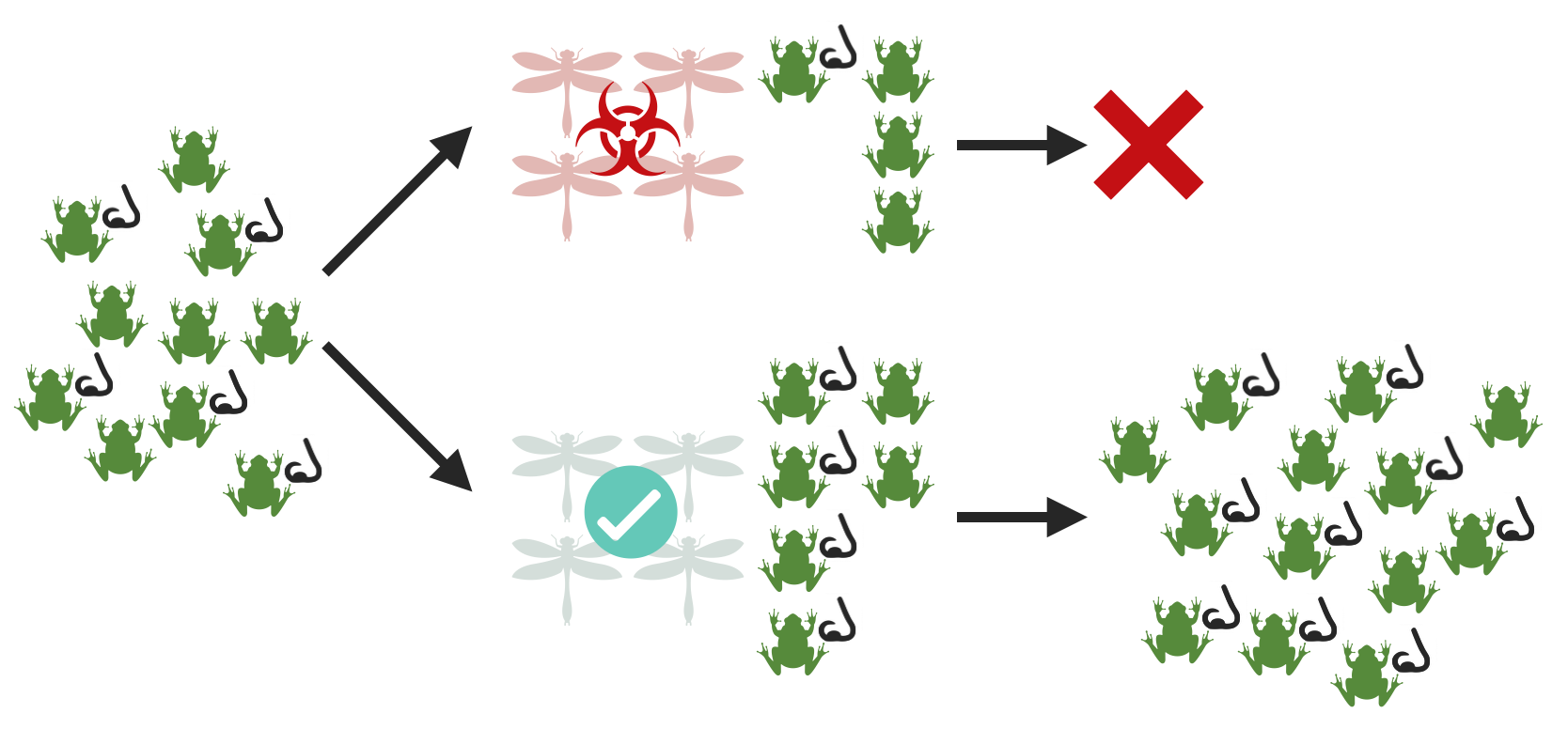

Evolution is not a goal-oriented process. Organisms can’t collectively think “our population will boom if we could better distinguish toxic from non-toxic food sources” and then develop a trait in response to that. They can’t try to evolve.

Yeah, the “goal” is to reproduce more, but organisms aren’t consciously making choices that will allow for more reproduction in later generations.

Instead, consider a population with individuals that vary in their senses of taste and smell. Heightened senses might prevent certain individuals from eating toxic foods, thereby allowing them to survive better and later reproduce. If their offspring can inherit the heightened senses, they might survive better than those without.

Over many generations, the species could improve its ability to distinguish toxic from non-toxic foods, but that was never the goal. It was simply a byproduct of heightened senses being advantageous in the moment. Natural selection just happens, naturally!

A starting population consists of frogs with heightened senses and frogs with normal senses. Those with heightened senses may be less drawn to toxic food sources, causing them to survive and reproduce more. Generations later, the frogs with heightened senses become the majority of the population. Image: AL Fortier.

So be wary of the phrasing you hear in the news. People tend to say things like “cheetahs evolved their incredible speed in order to catch prey.”

But there was no grand design for the cheetah—instead, faster cheetahs had an advantage in catching prey (and therefore were eating well, surviving longer, and passing the genes that made them faster to more babies), so the species evolved to be faster over time.

EVERY TRAIT HAS AN EASY EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATION.

Not every characteristic can/should be explained retroactively. Consider the human nose. An outside observer of humanity might guess that the nose evolved in order to hold glasses, because all glasses rely on a protruding nose to stay in position.

But in reality, there were a lot of complex forces involved in shaping the human nose. For one, its shape was somewhat constrained by the nose shape (and overall face structure and body plan) of our ape ancestors. The nose is also an important part of breathing, smelling, and filtering out pathogens and debris.

All of these forces were likely involved in the evolution of the nose. Considering “glasses-holding ability” apart from these other factors is much too narrow of a view.

So while it’s tempting to just say “the nose evolved to hold glasses” and call it a day, we have to remind ourselves that evolution doesn’t happen with a goal in mind (see above). And we also have to be careful not to oversimplify things or try to explain a trait in isolation.2

CERTAIN SPECIES ARE “MORE EVOLVED” THAN OTHERS.

There is no grand plan for making species. Species evolve certain traits often because those traits happened to improve survival and reproduction at one point in time.

A lot of people view humans as “more evolved” than sea sponges, for example. Sea sponges are stationary ocean animals often mistaken as “primitive” because they form a sister group to all other animals. This means that all animals came from an ancestral species that split into two groups a long time ago. One group evolved into modern-day sea sponges, and the other group evolved into all other animals—everything from jellyfish, to microscopic plankton, to giraffes, to humans.

Because sea sponges are the sister group to us and all the other animals, people assume that other animals have been changing and evolving while the sponges stay the same. But in reality, it’s taken just as much time (over 700 million years!) for the ancestral species to become modern sea sponges as it has for that same species to become human.

And humans are by no means “optimal” - like the sponges and all other species, we’re continuously evolving.3

EVOLUTION MAKES SPECIES “BETTER.”

Beneficial traits are more likely to evolve, but detrimental ones can evolve too.

For one, this can happen when a trait is good in one context but bad in another. For example, a mutation that gives people resistance to malaria also causes sickle-cell disease. In areas where malaria is common, this mutation is beneficial, while in areas without malaria, it is detrimental.

Another possibility is that the environment changes more quickly than evolution can keep up with, making previously-beneficial things now detrimental. For example, the peppered moth originally evolved a speckled white color, allowing the moths to hide from birds on white birch trees.

White peppered moths can hide from predators on birch trees. Image: Wikipedia.

The black coloration evolved in response to dark soot covering the trees. Image: Wikipedia.

But during the industrial revolution, black soot covering everything made it easier for birds to find and eat the white moths, and black moths began to evolve. The white color that was good for hiding was now detrimental! (With modern clean-air laws and less soot, the white speckled individuals are now making a resurgence.)

Evolution can also increase the frequency of traits that are neither good nor bad—just neutral. For example, red hair in humans arose relatively recently. As far as we know, red hair doesn’t make humans survive longer or have more children.4 It has just increased in frequency over time due to random chance.

EVOLUTION MAKES SPECIES MORE COMPLEX.

It’s really hard to define “complexity” when talking about organisms. Most people would agree that a human is more complex than a single-celled bacterium, but how would you compare a tiger and a whale? Or two different species of bacteria? Or a coral and an oak tree?

Could we define complexity according to genetics? The size of the genome and the number of genes varies widely, even among similar species. So evolving a bigger genome doesn’t necessarily correspond to “complexity.”5

And traits can be gained—for example, the ability to see in color, take advantage of a new food source, move around, or convert light into usable energy. But traits can be lost too. Like how fish species that inhabit pitch-black caves lost functional eyes once their vision was no longer essential. And apes (including humans) lost the gene that once allowed us to make our own Vitamin C, once our diets became nutritious enough to render it unnecessary. So evolution doesn’t always act to increase the number of traits, either.

Complexity is a vague concept to begin with. And even if we could define it, we know that evolution doesn’t always make things more complex, just different.

EVOLUTION CAN HAPPEN IN A SINGLE INDIVIDUAL.

A racoon learning that trash cans contain food, a human gaining muscle mass, a dog training for a trick, or a flamingo becoming pink because of the food it eats, are NOT examples of evolution. These changes occur in a single individual in a single generation and cannot be passed down genetically, so they are not evolution.

However, there are genes that affect dogs’ learning and memory. So the ability to learn tricks CAN be passed down, and it’s possible for dogs as a species to evolve better learning ability over time. This IS an example of evolution.

So while a specific dog learning a new trick is not evolution, its ability to learn in general is the product of evolution.

Similarly, racoons have genes that allow them to smell certain things and thus locate food, which is inherited. So racoons as a whole could evolve to become more attuned to the smell of trash cans over time, which is also considered evolution. While a particular raccoon identifying a specific dumpster as a source of food is not evolution, its ability to smell out food sources is the product of evolution.

HUMANS CAN’T HURT ECOSYSTEMS, BECAUSE ORGANISMS WILL JUST EVOLVE.

Organisms can certainly evolve in response to environmental change, but they have to have a starting point.

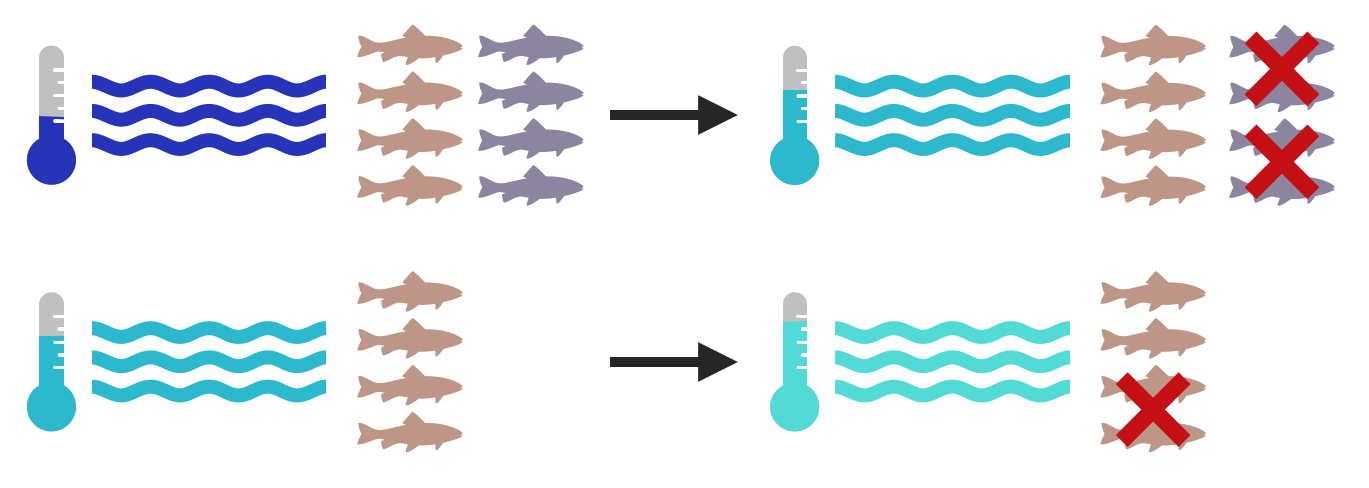

For example, consider two fish species: one has a huge habitat range including both cool and warm waters, and the other is limited to very cold ocean waters.

The first fish species is more likely to survive in spite of global warming, because individuals that can tolerate warmer waters already exist in the population. As waters warm, these individuals might survive and have babies—natural selection!

The brown fish species can survive in both cool and warm waters, while the purple species can only survive in cool waters. Global warming will warm all waters. The brown fish species can survive because it already had fish that were able to tolerate warmer waters, while the purple fish species dies out. Image: AL Fortier.

The second species is more likely to go extinct. If none of the individual fish of that species have the ability to tolerate warmer temperatures, then rapidly-warming waters would just kill all the fish. There would be no warm-water-tolerating fish that could be naturally selected for in the first place.

So pressures from humans can—and do—hurt ecosystems and drive species extinct.

CONCLUSION

So, if you put a frog in a desert, could it become a gazelle? Can you identify bus guy’s misconceptions about evolution?

One, evolution can’t act on a single, individual frog. You’d need a whole population reproducing over multiple generations. Two, evolution isn’t acting to produce something specific, like a gazelle. A group of frogs could potentially evolve there, but only in ways that improved their immediate survival-and-reproduction ability. Gazelle-like features probably aren’t what this environment would favor. Third, the frogs probably don’t have the ability to survive in such a drastically different environment. If a few of the frogs happened to better tolerate less water, hotter temperatures, or avoid desert predators, then these particular traits could evolve in the population over time. But chances are, the frogs’ existing variation just couldn’t cover it, and all of them would die before evolution could even occur.

So, the answer is a definite no.

FURTHER READING

Even More Evolution Misconceptions!

REFERENCES

[1] Itan, Yuval, et al. “The Origins of Lactase Persistence in Europe.” PLoS Computational Biology, vol. 5, no. 8, 28 Aug. 2009.

[2] Gould, S. J., and R. C. Lewontin. “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, vol. 205, no. 1161, 1979, pp. 581–598.

[3] Pennisi, Elizabeth. “Humans Are Still Evolving-and We Can Watch It Happen.” Science, 17 May 2016.

[4] Harding, Rosalind M., et al. “Evidence for Variable Selective Pressures at MC1R.” The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 66, no. 4, Apr. 2000, pp. 1351–1361.

[5] Eddy, Sean R. "The C-value paradox, junk DNA and ENCODE." Current biology, 22.21 (2012): R898-R899.