HE WHO HESITATES IS LOST

COVID VACCINES MINISERIES PART 5: NOT QUITE PRO-VAXX, NOT QUITE ANTI-VAXX: THE VACCINE-HESITANT

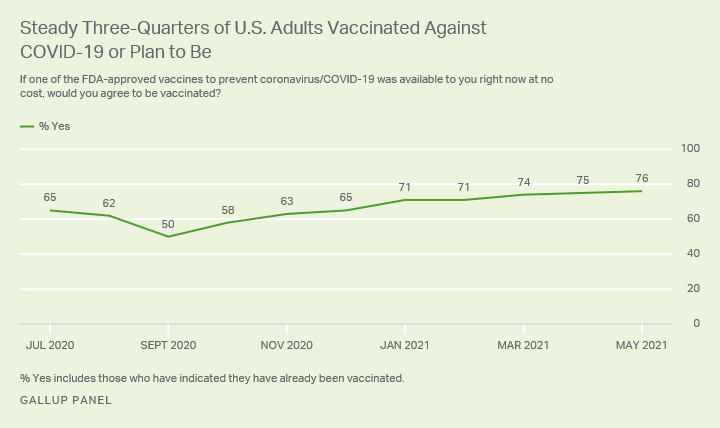

Declining vaccination rates in the United States have led to numerous preventable outbreaks in recent years. Even diseases once completely eliminated from the country, like measles, mumps, rubella, whooping cough, and chicken pox, have made a resurgence. 1 Since anti-vaxxers often collect in small pockets, their beliefs are directly to blame for many of these epidemics. For example, anti-vaxx communities in New York and Washington state were the source of major measles outbreaks in 2019 - the largest outbreaks since the disease was eradicated in the US in 2000. 2,3 Even more concerning, anti-vaxxers’ influence is increasing. One study of over 100 million Facebook users showed that anti-vaxx groups have more connections to undecided populations and are growing faster than pro-vaccine groups. 4 Despite their large influence, anti-vaxx groups are still in the minority - so why are COVID-19 vaccination rates stagnating? It all comes down to the vaccine-hesitant. Gallup polls show that about 20% of Americans will probably not get the vaccine. This group includes everyone who wants to “wait and see” and those who will “maybe” get the vaccine, in addition to those staunchly opposed. 5,6 There are numerous, nuanced factors that prevent people from jumping eagerly in line to receive a vaccine. But just because they’re not as extreme as anti-vaxxers doesn’t mean they’re any less dangerous - the World Health Organization considers vaccine hesitancy one of the top threats to global health for the next decade. 7 In this part of our COVID-19 Vaccines miniseries, we’ll explore the reasons for vaccine hesitancy and show you how to combat this very-real threat in your personal network.

Figure 1: Gallup Polls show that vaccine acceptance in the US has mostly stagnated.

BARRIERS TO ACCESS

Soon after the 3 COVID-19 vaccines were approved, there simply were not enough to go around. The US’s vaccine rollout plan prioritized people by age group, pre-existing conditions, and type of employment, before eventually opening up to everyone 12 years or older. Now, there’s enough supply to vaccinate the entire US population 5 times over - the vaccines are here, but where are the arms to receive them? 5

One often-understated problem is persistent barriers to access. In 2018, only 73.2% of children without health insurance had received the MMR vaccine, compared to 93.7% of privately insured children. 8 Poverty and inequitable access to care prevents a lot of people, particularly in countries with privatized health insurance, from receiving vaccines. In the United States, the burden of these inequities falls mainly on people of color. 9 Although the COVID-19 vaccine is free with or without insurance, some people fear that if they were to get a rare side effect, they’d have to pay exorbitant medical bills for seeing a doctor later on. 10 Uninsured people are also less likely to be connected with a regular healthcare provider, who would normally serve as a resource for information about the vaccine. 11 In addition, some people simply cannot afford the 24-48 hour long flu-like side effects that occur after getting the vaccine - they have to work or take care of their children or elderly parents. 10 And non-health-related barriers, like transportation to vaccination sites, can prevent even more people from accessing the vaccine. Hospital and pharmacy “deserts”, rural areas without medical facilities for miles, mean getting to a vaccination site could be an exhausting journey. Vaccination sites also tend to be located away from communities of color, making inequities even worse. 11 Other people are not impeded by physical barriers, but instead by providers’ attitudes. In areas where healthcare providers have opted not to get the vaccine themselves, they are unlikely to promote the vaccine to their patients. 10 This directly impacts people who rely on their main healthcare provider for vaccine information. All of these systemic barriers to access mean that for some people, getting vaccinated isn’t a walk in the park.

DISTANCE FROM THE ISSUE

Another subgroup of the vaccine-hesitant is better called “vaccine indifferent” - these people don’t actively think about COVID-19, either because they live in a rural area with few cases, they don’t have children in school, or their job doesn’t require them to interact with many people. In addition, speaking a different language, not using social media, or not reading the news can further prevent people from engaging directly with the pandemic. 10 For this group, a COVID-19 vaccine is simply not on their radar.

Other vaccine-indifferent people think that the vaccine isn’t really meant for them, either because they are young, believe they are healthy, or don’t plan on traveling or being in crowds. Others believe that masks, social-distancing, hand-washing, or taking vitamins is sufficient, and vaccines are simply not necessary if they comply with these other requirements. 10 Related to this is the issue of mixed messaging. Official recommendations regarding COVID-19 have changed rapidly over the pandemic due to changing evidence. Although this is a natural and necessary part of scientific progress, it has also left many people confused. Relaxing mask requirements and travel restrictions over the last couple months indicated the “end” of the pandemic for many, causing them to think vaccination was no longer necessary. 12 But the pandemic is still very much a problem and vaccination is still the best way to prevent the spread of the virus, severe complications, and death.

SYSTEMIC DISCRIMINATION

Specific communities also have their own reasoning for vaccine hesitancy. For example, surveys have found that African Americans living in Alabama view the vaccine as just as bad as getting COVID-19. 10 Black people in the US have historically been treated unfairly in medicine, including being experimented on without their consent. In the Tuskegee experiment, Black people with syphilis were not told they had the infection and were not given treatment despite the fact that antibiotics were readily available at the time. 9 As another example of medical mistreatment, Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman with cervical cancer, had her cells taken without her knowledge or consent and turned into a profitable source of cell cultures used in scientific research. 13 Aside from these grievous exploitations, Black people also endure higher rates of conditions like pregnancy-related complications and diabetes, constant stress and health problems due to systemic racism, and biased healthcare providers who ignore patients’ concerns or even actively belittle them. 9 It’s no surprise that historical and current mistreatment of Black Americans has made them skeptical of the vaccine. In addition, some remain concerned that the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been given to African Americans at higher rates than the other two vaccines. They worry they are being given a lower-quality vaccine because the Johnson & Johnson vaccine’s reported effectiveness is lower than the other two vaccines (in reality, effectiveness numbers are not directly comparable; see Part 2). 10 Rest assured, all three vaccines are safe and effective, and getting any one of the three is critical to ending this pandemic.

Figure 2: Joe and Jill Biden independently visited vaccination sites across the US South to increase vaccine confidence. Photograph: Tom Brenner/Reuters

PARTISANSHIP

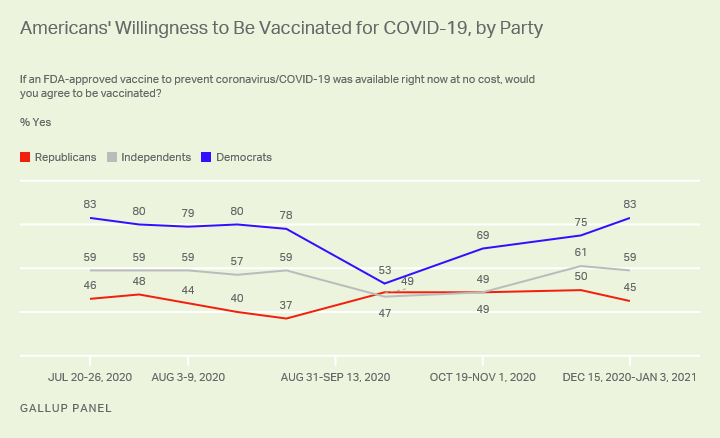

In the United States, political affiliation is the number one indicator of vaccine hesitancy. 46% of Republicans and 31% of independents say they won’t get the vaccine, compared to 6% of Democrats. 6 Since rural areas tend to lean Republican, this explains why rural communities have had less vaccine uptake as well. 11 The reasons for this divide are also complex - Republicans tend to have less faith in science, the government, news media, and academic institutions, making this group less likely to believe any vaccine-related information coming out of these sources. 6 Former president Donald Trump also has a complex sway over his Republican followers’ perspectives. Trump consistently understated the threat of COVID-19 throughout 2020, even after he contracted the virus himself. He also publicly promised to speed up vaccine rollout in the weeks preceding the 2020 election, which sharply increased vaccine hesitancy among both Republicans and Democrats. Later, Trump himself received the vaccine and publicly encouraged his own voters to get it, despite months of saying the opposite. 5 Although Trump ultimately changed his mind, months of political polarization regarding the pandemic has cemented many Republicans’ hesitancy toward the vaccine.

Figure 3: Vaccine acceptance is much higher among Democrats than Republicans, although both dipped significantly nearing the 2020 presidential election. Gallup poll.

AROUND THE GLOBE

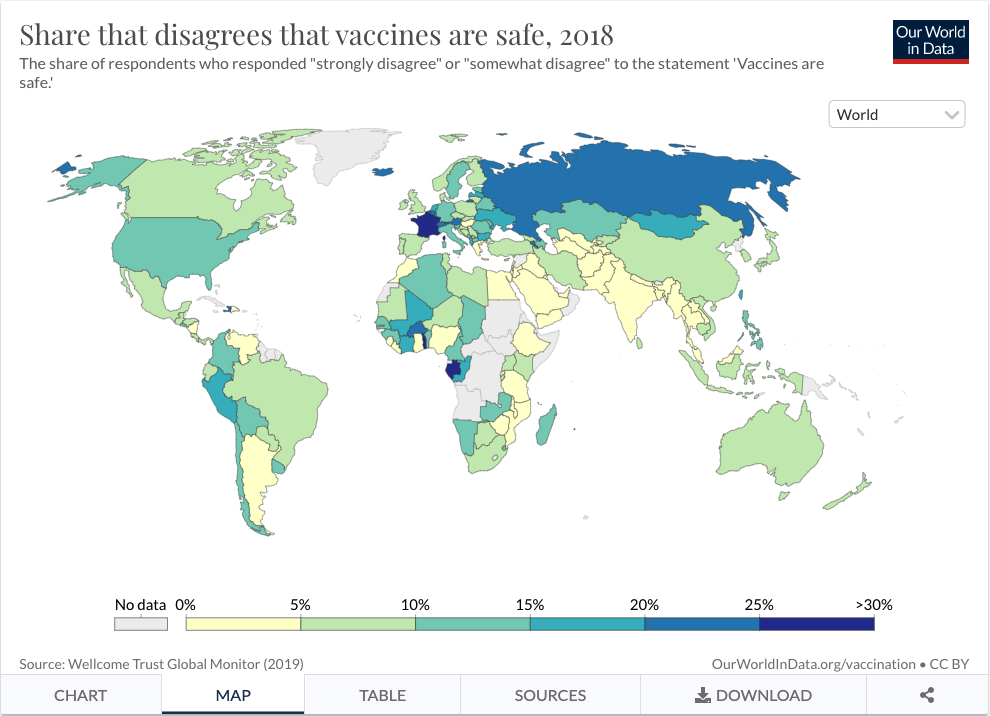

Vaccine hesitancy isn’t limited to the United States, either. Distrust and rumors led to a boycott of the Polio vaccine in Nigeria, causing Polio outbreaks in 3 continents. The lack of information provided by healthcare providers is the main reason for vaccine hesitancy in Latin America and the Caribbean. In the Philippines, fears over side effects, caused by a failure to properly communicate risk, prevent people from getting the Dengue vaccine. 14 Regarding COVID-19 vaccines specifically, the Tanzanian president publicly doubted the existence of COVID-19 and the effectiveness of the vaccines, and as a result, refused to develop a vaccination plan for his citizens. Luckily, his successor, who took office in March 2021, has since begun vaccine rollout. 15,16 In Nigeria, one state secretary talked about the dangers of vaccines on an official panel and continues to share anti-vaccine sentiments online, while a top Nigerian pastor also uses his internet influence to spread vaccine conspiracy theories. The rise of anti-vaxxers in Africa is partially due to increased internet access over the past 5 years, allowing more and more people to access social media and get connected with communities all over the world. 15 Because misinformation can now travel globally in an instant, it is becoming harder and harder to contain anti-vaccine sentiment.

Figure 4: Vaccine hesitancy is increasing in richer countries, such as in the US, Canada, and much of Europe. Our World in Data.

COMBATING VACCINE HESITANCY

Vaccine hesitancy is a complicated issue, and there’s no one-size-fits-all-approach to combating it. On a government or community scale, approaches include engaging religious or traditional leaders, mass media, one-on-one communication between individuals and healthcare providers, or more personalized approaches. In the United States, the Biden administration has prioritized door-to-door community outreach, encouraged primary care doctors to administer vaccines in the clinic, set up mobile clinics, helped adolescents get access to vaccines, and urged workplaces to change their policies. 17 All of these measures should make it easier for everyone, including those facing the greatest inequities, to receive their vaccine.

Other strategies include providing positive incentives, like gift cards, raffle entries, or free Krispy Kreme doughnuts. 14 Negative incentives can also work, like requiring vaccine passports for travel, dining in restaurants, riding public transit, or attending schools and universities. Governments can also issue vaccine mandates (as we learned in Part 3, the Supreme Court deemed this constitutional in the US). Despite the amount of pushback a mandate would receive, it could be quite effective at reducing cognitive dissonance - people can justify getting the vaccine because they had to, rather than grappling with the choice themselves. 6 More personalized approaches, like sending vaccination reminders by call or text, can also ease the burden of signing up and help people navigate the confusion. 14

Figure 5: Krispy Kreme Doughnuts currently offers an incentive for getting vaccinated.

All of these strategies can increase access and motivation, but they may not improve people’s feelings toward the vaccine itself. In the long run, improving people’s confidence in science and vaccination will decrease the chance of future outbreaks and pandemics. Strategies for improving vaccine confidence have to be religiously, historically, and culturally sensitive, while addressing the specific fears and needs of each community. 14 For example, in the United States, engaging church groups has been fairly successful. Forums on vaccine use, encouragement from faith leaders, photographs of religious leaders getting vaccinated, and even setting up vaccination centers in churches have all improved vaccine acceptance in religious communities, particularly among Protestants of color. 18 Reverend Jesse Jackson even received his vaccine on live TV, increasing confidence among religious African Americans. 15 Religious approaches might also be effective at closing the partisan divide. Since white protestants are generally Republican, and Republicans tend to have much more trust in faith institutions than the government, they may be more likely to take a vaccine endorsed by or administered at their church. 6

Yet a similar approach failed in Nigeria. When several government officials flew to other countries to get vaccinated on TV, people wondered whether the vaccine offered in those countries was the same one being given to them. A better approach to increase vaccine confidence in Africa seems to be publicizing positive stories, such as the successful vaccine rollout in Morocco, Rwanda, Angola, and Ghana 15 . Successful strategies to improve vaccination rates vary widely depending on culture and context.

You probably aren’t directly involved in the community-level strategies unless you’re a lawmaker or community leader. But you can still increase vaccine confidence in your personal circles. The Center for Countering Digital Hate recommends boycotting the social media platforms that have refused to remove or flag misinformation, which will hopefully scare advertisers away and prevent anti-vaxx groups from making money. 19 You can also report offending social media posts or groups, so people you are loosely affiliated with are less likely to see them. If you want to take a more active approach, you can try to rebut anti-vaxx arguments, either online or in conversations. 19 The common arguments, along with their flawed reasoning, are listed in Part 4. However, experts disagree on the effectiveness of this approach. Most anti-vaxxers are pretty convinced of their beliefs, so you aren’t likely to change their minds. 19,20 Engaging with extremely flawed arguments online could even be counterproductive, as it can make a post more popular and more likely to appear in other peoples’ news feeds. 19,20

But what if the person you’re arguing with isn’t anti-vaxx, just vaccine hesitant? Most vaccine-hesitant people cite worries about side effects, so presenting reputable sources with success statistics might seem like the right move. But this ignores the fact that many of these people do not have faith in the institutions that produced the data in the first place. Even if the person you’re talking to doesn’t have a particular distrust in science, they may not be used to assessing scientific evidence or having rational debates 6 . In many of these cases, having all the data in the world would still fail to make an impact. Additionally, the vaccine-hesitant are often typecast as stupid or ignorant, so accosting them with data might feel condescending. Approaching people with respect and engaging in a two-way conversation, rather than just spewing facts, is a better tactic. 20,21 Offer a safe space to talk and show respect for the person’s feelings while also assuaging their fears - hopefully they’ll come away from the conversation feeling positive. 21 Online, consider collecting questions anonymously and answering them on your platform or advertising a safe place where people can come to you without fear of judgement. 20

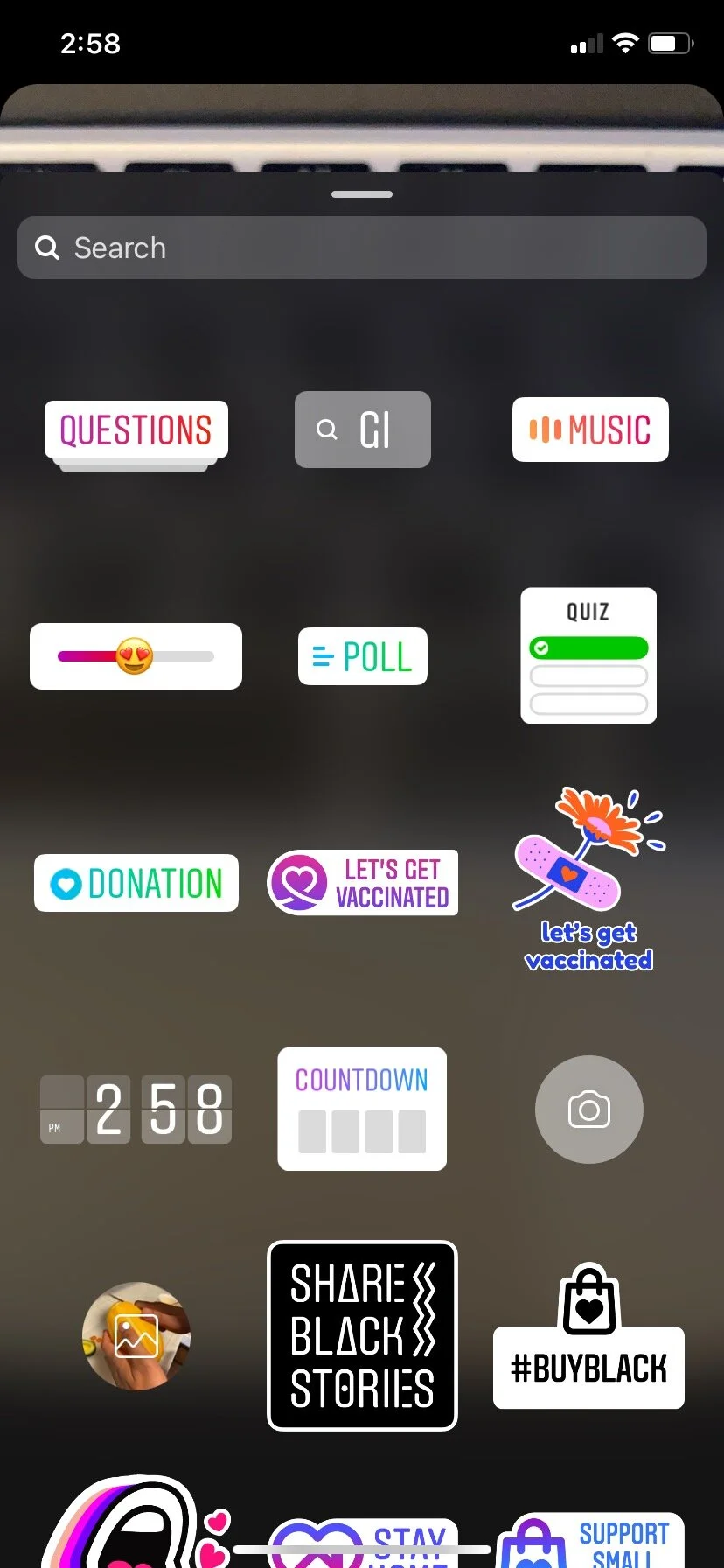

Having conversations with vaccine-hesitant people in your own life will certainly make an impact, but we need millions more people to get vaccinated in order to reach herd immunity. Normalizing vaccination seems to be the easiest way to get people on board, though it may take a long time. If something becomes normalized in society, it takes a lot of care and effort to avoid doing it, but almost no effort to just do it. While this may not work for the most fanatical anti-vaxxers, normalizing COVID-19 vaccination, along with increasing access, will eventually convince most of the hesitant. 5 Instead of fighting in the comments or sharing an anti-vaccine post to make fun of it, consider instead sharing good information from trusted sources. You can also post pictures or videos of yourself getting vaccinated to show others that it’s nothing to fear. 20 A lot of people are vaccine hesitant because they want to see other people get their vaccine first or have heard scary claims online that they don’t fully understand. Showing that you’re vaccinated and combating misinformation in a respectful and positive way is a critical step toward fighting this public health crisis.

Figure 6: Instagram offers “Let’s get vaccinated” stickers to encourage users to spread positive vaccine stories over social media.

CONCLUSION

In this series, we’ve explained the science behind COVID-19 vaccines, the numbers behind their safety and efficacy, the history and tactics of the anti-vaxx movement, and contemporary reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Next week, we’ll talk about the delta variant - what it is, where it came from, and why it’s such a threat. The most important thing we can do right now to stop this pandemic is get vaccinated, so please share this series with your vaccine-hesitant friends and family. Let’s end this thing and get back to normal life!

REFERENCES

Ortiz, Jorge L. “Anti-Vaxxers Open Door for Measles, Mumps, Other Old-Time Diseases Back from near Extinction.” USA Today, 1 Apr. 2019, eu.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2019/03/28/anti-vaxxers-open-door-measles-mumps-old-time-diseases/3295390002.

Rayes, Raneem. “America’s Measles Crisis Amid the Anti-Vaccine Movement.” The Public Health Advocate, Berkeley Public Health, 2019, pha.berkeley.edu/2019/12/01/americas-measles-crisis-amid-the-anti-vaccine-movement.

“CDC Newsroom.” CDC, 25 Apr. 2019, www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/s0424-highest-measles-cases-since-elimination.html.

Johnson, Neil F., et al. “The Online Competition between Pro- and Anti-Vaccination Views.” Nature, vol. 582, no. 7811, 2020, pp. 230–33. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1.

Engber, Daniel. “America Is Now in the Hands of the Vaccine-Hesitant.” The Atlantic, 23 Mar. 2021, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/03/america-is-now-in-the-hands-of-the-vaccine-hesitant/618352.

Newport, Frank. “Vaccine Hesitancy and U.S. Public Opinion.” Gallup.Com, 30 July 2021, news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/352976/vaccine-hesitancy-public-opinion.aspx.

Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Tedros. “Urgent Health Challenges for the next Decade.” World Health Organization, 13 Jan. 2020, www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/urgent-health-challenges-for-the-next-decade.

Leask, Julie. “Vaccines — Lessons from Three Centuries of Protest.” Nature, vol. 585, no. 7826, 2020, pp. 499–501. Crossref, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02671-0.

Santhanam, Laura. “5 Stories about COVID-19 Vaccine Mistrust from Americans of Color.” PBS NewsHour, PBS, 24 Feb. 2021, www.pbs.org/newshour/health/for-americans-of-color-considering-the-covid-19-vaccine-heres-why-trust-is-so-important.

Sobo, Elisa J., et al. “Black and Latino Communities Often Have Low Vaccination Rates – but Blaming Vaccine Hesitancy Misses the Mark.” PBS NewsHour, PBS, 8 July 2021, www.pbs.org/newshour/health/black-and-latino-communities-often-have-low-vaccination-rates-but-blaming-vaccine-hesitancy-misses-the-mark.

Oladipo, Gloria. “US Fight against Covid Threatened by Growing Vaccine Gap in the South.” The Guardian, 27 June 2021, www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/27/us-covid-vaccine-disparities-south.

Blamont, Matthias, et al. “After Vaccination Burnout, Delta Variant Spurs Countries to Speed up Shots.” Reuters, 13 July 2021, www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/after-vaccination-burnout-delta-variant-spurs-countries-speed-up-shots-2021-07-13.

“Henrietta Lacks: Science Must Right a Historical Wrong.” Nature, vol. 585, no. 7823, 2020, p. 7. Crossref, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02494-z.

Simas, Clarissa, and Heidi J. Larson. “Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy in Low-Income and Middle-Income Regions.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00279-w.

Adepoju, Paul. “Africa Is Waging a War on COVID Anti-Vaxxers.” Nature Medicine, 2021. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01426-2.

Mwai, Peter. “Covid in Tanzania: Vaccination Campaign Gets Underway.” BBC News, 28 July 2021, www.bbc.com/news/57641824.

Stolberg, Sheryl Gay, and Michael Shear. “Covid News: Biden Calls For New Vaccination Push.” The New York Times, 14 July 2va021, www.nytimes.com/live/2021/07/06/world/covid-19-vaccine-coronavirus-updates.

Jenkins, Jack. “Vaccine Hesitancy Declines among Faith Groups, Spurred Partly by Religious Appeals.” The Salt Lake Tribune, 28 July 2021, www.sltrib.com/religion/2021/07/28/vaccine-hesitancy.

Burki, Talha. “The Online Anti-Vaccine Movement in the Age of COVID-19.” The Lancet Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 10, 2020, pp. e504–05. Crossref, doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(20)30227-2.

Ahmed, Imran. “Dismantling the Anti-Vaxx Industry.” Nature Medicine, vol. 27, no. 3, 2021, p. 366. Crossref, doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01260-6.

Robson, David. “Why Some People Don’t Want a Covid-19 Vaccine.” BBC Future, 22 July 2021, www.bbc.com/future/article/20210720-the-complexities-of-vaccine-hesitancy.